This article is part of Brainscape's Science of Studying series.

You know that annoying thing your roommate does when they plonk down on the couch next to you, right in the middle of your favorite show, and ask you… “What’s it about?” My personal revenge story is to hit the pause button, turn to them, and regale them in excruciating detail what it’s about, right from the pilot up to season 4, episode 9.

Approximately 37 seconds later, they bounce back up saying “sheesh, sorry I asked!”

So, to answer the question posed in the title of this article, free recall is a delicious weapon of vengeance.

A more universal application of free recall, however, is in learning, where it provides students of any subject with a simple yet powerful way to ingrain information really quickly and effectively.

And that’s what this article is about: the simple learning hack that empowers you to solidify anything you’re learning, turning it from familiarity into mastery FAST.

In this guide, we’ll unpack what free recall is, why it’s one of the most accurate mirrors of what you truly know, and how to train your brain to perform it more reliably, whether you’re studying, teaching, or designing learning experiences for others.

So, if you want to learn faster, you’ve got to master free recall.

Let’s go!

What Is Free Recall?

Free recall is the act of retrieving information from memory without any external prompts or cues. In my example, I was recalling my show’s plot, subplots, and characters, right from episode 1 until present. In practice, as a student, it would look more like:

- Getting home from school or college and attempting to recall from scratch everything you learned in class that day.

- Reading a textbook chapter or watching a lecture, and then attempting to explain everything you just consumed in detail (without referring back to the material).

- Studying a deck of flashcards on a particular topic, and then using your afternoon treadmill run to recite everything you can remember from the entire deck.

The key here is that beyond the topic choice, you are receiving no cues. No assistance. No crutches. Free recall gives you no hint about what the answer might look like. You must generate it entirely from memory, providing detailed and layered explanations atop a strong conceptual foundation.

You have to know a subject pretty well in order to do this. And that’s exactly the point of free recall. It compels you to know thy subject!

In learning science, free recall is central to understanding the difference between familiarity and mastery. Students often believe they know something because it seems familiar during review. They think: “Yes, I’ve seen this before! I must know this.”

But familiarity is not memory. Free recall is.

So, try this: Whatever you’re currently learning, pick a chapter, module, or broad subject area. Now, without looking at your materials, explain it from the ground up, defining all of its constituent parts, as though to someone totally ignorant. Speak it aloud in terms even a 5th grader would understand.

Congratulations. You just did free recall. (And your knowledge of that subject will be stronger for it.)

What is the Feynman Technique?

It turns out this way of learning is so effective that it’s famously associated with none other than Richard Feynman, the Nobel Prize–winning physicist known not just for his brilliance, but for his uncanny ability to explain complex ideas in plain English. Feynman was a relentless advocate of understanding things so clearly that you could explain them to a child, and his approach later became popularized as the Feynman Technique.

At its core, the Feynman Technique is essentially free recall with a clarity constraint. You take a concept, close your notes, and explain it as if you were teaching it to a fifth grader. No jargon. No hand-waving. No “you know what I mean.” If you get stuck, use vague language, or realize you’re leaning on memorized phrases instead of real understanding, you’ve just discovered a gap worth fixing.

That act of explaining from memory—simply, completely, and in your own words—is exactly what makes both free recall and the Feynman Technique such brutally effective learning tools.

Now, as someone who is curious enough to get this far into a geeky article on the cognitive science of studying, you’re probably wondering…

What’s the Difference Between Free Recall, Active Recall, & Cued Recall?

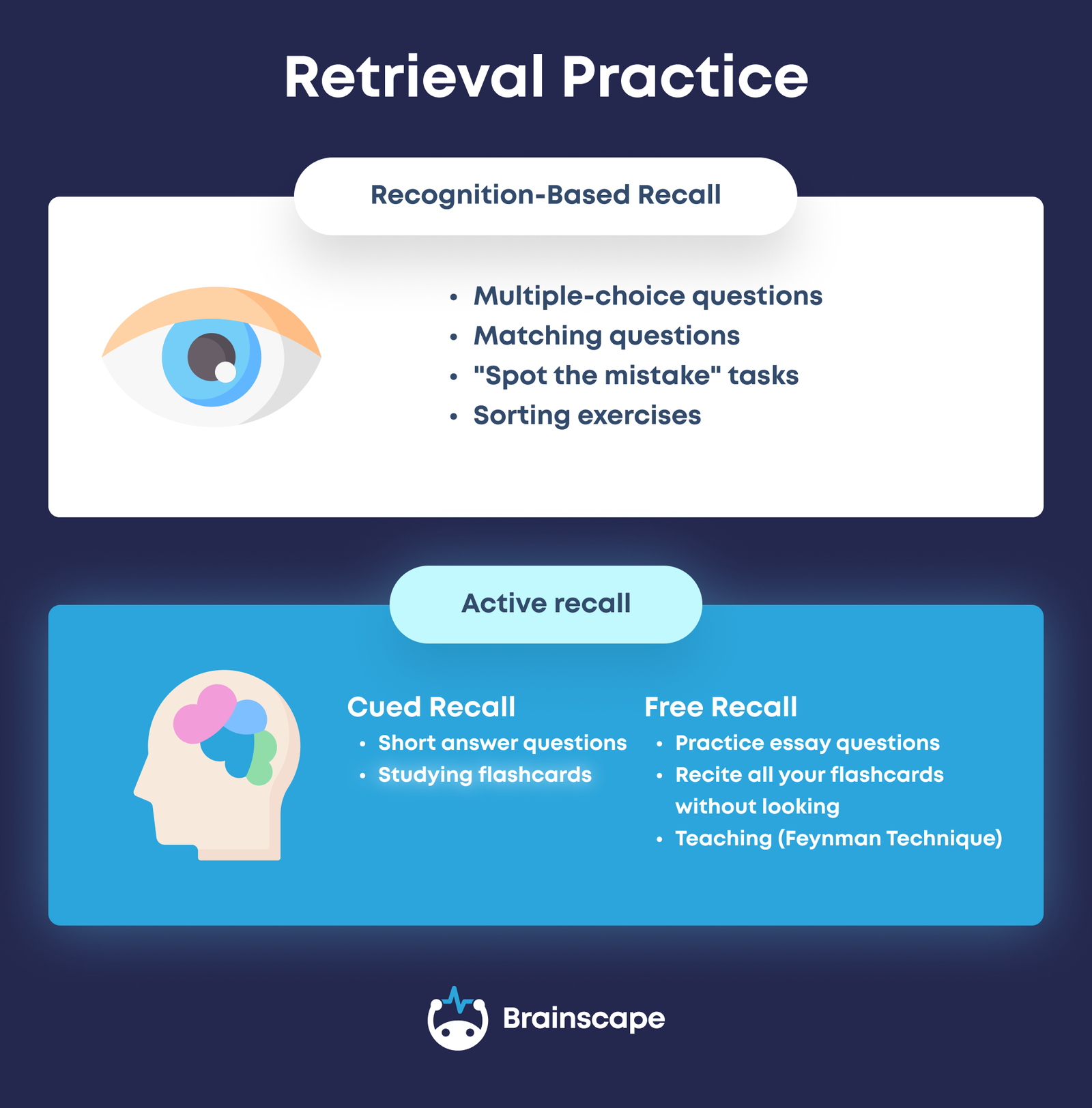

These three terms sit under the umbrella of retrieval practice, the family of study techniques that strengthen memory by pulling information out of your brain rather than pushing more information in. But they differ in how much assistance or prompting you get during the retrieval process.

Free recall, as we’ve just discussed, is the purest and most demanding form of retrieval practice. You receive no cues at all. e.g. Closing your notes, and trying to write everything you remember about photosynthesis or the Treaty of Versailles, is free recall. Because it provides no scaffolding, it reveals the truest picture of what you’ve actually learned, and it strengthens memory the most.

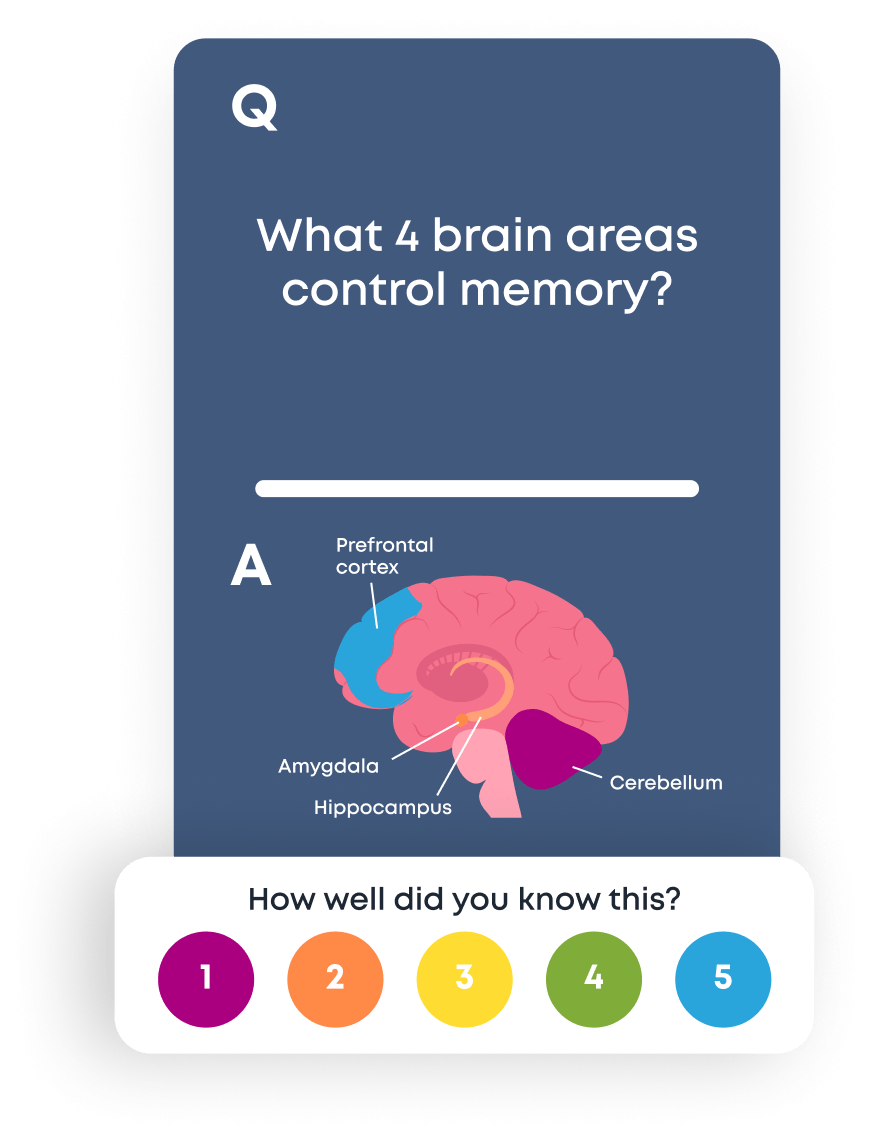

Cued recall provides a helpful nudge. You’re given a prompt—a question stem, a partial phrase, an image, or a category—and you must fill in the missing information. Flashcards, practice questions, and fill-in-the-blank tasks often fall into this category. Because cues guide the search process, cued recall requires less effort than free recall, but still far more than recognition tasks like multiple-choice questions.

Active recall is the broader term that includes any attempt to remember information without passively rereading it, including both free recall and cued recall. And as retrieval research consistently shows, the more effort your brain invests in remembering, the stronger and more durable your learning becomes.

Why Does Free Recall Matter for Learning, Teaching, & Memory?

Free recall is one of the most honest mirrors learning science has ever handed us. It strips away hints, scaffolds, and comforting familiarity and asks a single, uncomfortable question: What can you actually remember when nothing is helping you? The answer turns out to matter a lot.

It reveals the truth about what you know.

When free recall enters the picture, illusions of competence don’t last long. Without cues, you quickly discover the gap between “this looks familiar” and “I can explain this clearly.” That moment of friction provides essential information on where your knowledge strengths and gaps lie and, therefore, where your study focus needs to be directed.

It deepens understanding.

Every free-recall attempt forces your brain to reconstruct ideas from memory. That reconstruction weaves concepts together, strengthening the mental pathways that support comprehension. Over time, knowledge evolves from a loose collection of facts into a tightly woven tapestry.

It accelerates long-term retention.

Decades of research show that retrieval-based learning beats passive review every freaking time, even when recall attempts are messy or incomplete. Struggling to remember something and then checking yourself strengthens memory far more than rereading ever could.

It supports transfer.

Because free recall focuses on meaning, context, and connectedness rather than isolated facts, it prepares knowledge to travel. Learners who practice recalling ideas from scratch are more likely to recognize when and how to apply them in new situations, rather than only in the exact format they were studied.

It builds metacognitive accuracy.

Free recall also sharpens your internal “knowledge radar.” Over time, learners become better at predicting what they truly know and what still needs work. This ability (called metacognition) is a cornerstone of effective studying and teaching, yet it rarely develops through recognition-based review alone.

Educators often underestimate just how much students lean on recognition-based tasks like rereading, highlighting, and nodding along. Free recall nudges learning away from familiarity and toward a deep subject understanding you can actually use!

How Do Digital Flashcards Engage Free Recall?

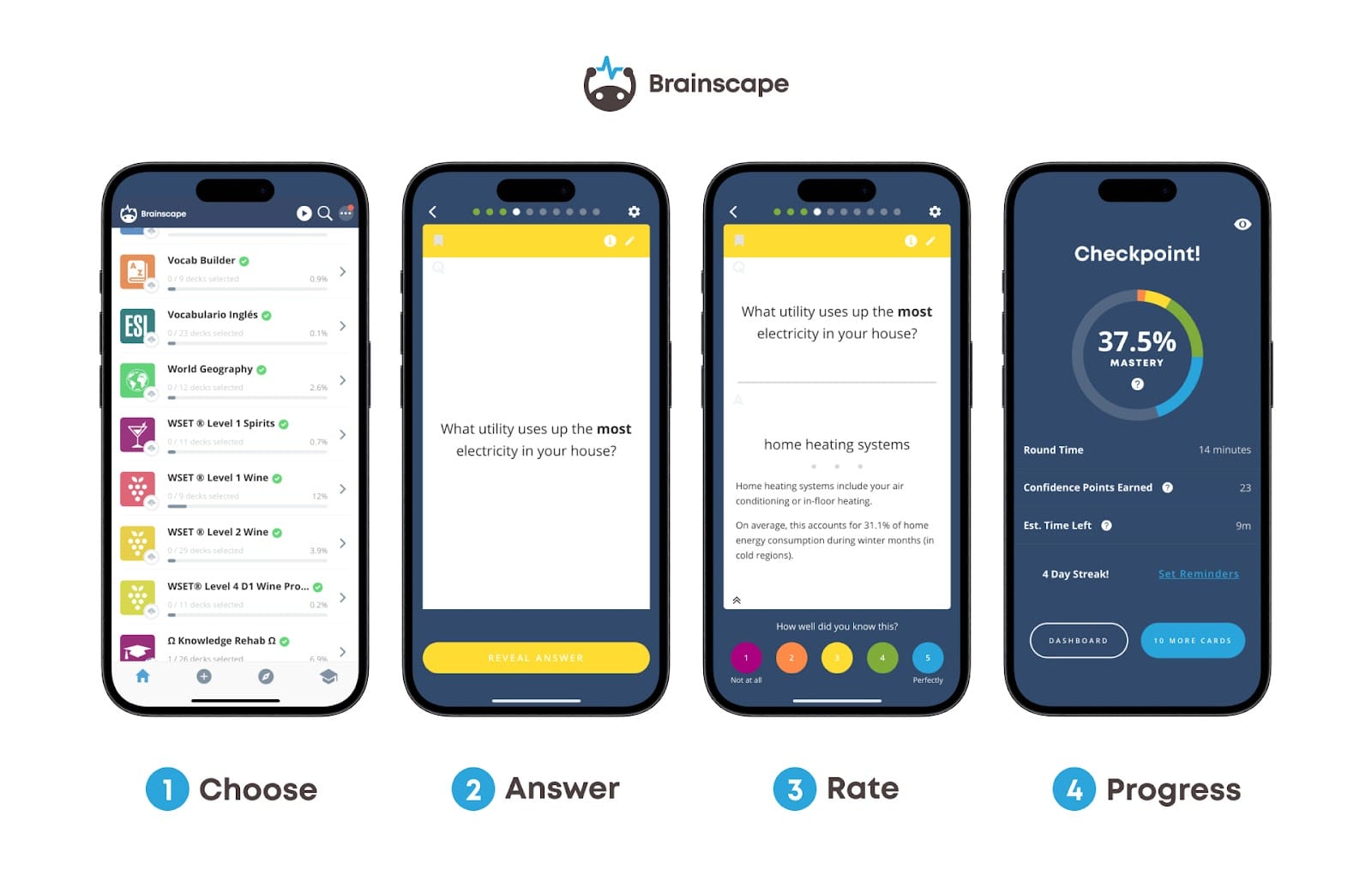

Let’s start with a simple truth: most people use flashcards for cued recall.

A classic flashcard gives you a prompt on the front and asks you to retrieve a specific answer on the back. Term → Definition. Or Question → Explanation. This is an excellent form of active recall, and it’s incredibly effective for building knowledge in the early and middle stages of learning.

But once you’ve reached roughly 70–80% mastery of a deck, something interesting happens. Continuing to flip through the same cards in the same way starts to produce diminishing returns, unless you space those sessions out over longer periods. 'Cause once you're at 70-80% mastery, your brain has gotten very good at answering that specific cue, but not necessarily at recalling the knowledge more freely or flexibly.

That’s when it’s time to level up to free recall. (Or the Feynman Technique if you recall that from earlier.)

Instead of opening the app and flipping more cards, put the flashcards down. Try to recite everything you remember from the deck—facts, concepts, examples, even the questions themselves—without looking. Go until you can’t go any further. Then return to the flashcards and flip through them to see what you missed, forgot, or distorted.

Those gaps are pure gold. Making a special note of them creates a powerful feedback loop that forges deeper and more durable memory connections than cued recall alone.

Want to go even more meta?

You can also design flashcards specifically for free recall. Instead of one narrow learning objective per card, create big-picture prompts like “Explain everything you know about cellular respiration” or “Walk through the causes and consequences of the French Revolution.”

On the back of the card, you can create a bullet-point list that touches on everything you should know about the topic, which, afterwards, you can quickly scan through to make sure you didn’t miss anything. (This is especially easy with digital flashcards, which aren’t constrained by physical space.)

These “zoomed-out” cards demand serious brainpower, but they work. They turn flashcards from simple cue-response tools into free-recall engines, helping you consolidate, integrate, and stress-test your knowledge at a much deeper level.

Digital flashcard systems like Brainscape or Anki are designed around these principles, helping you to train your powers of free recall in a consistent, painless way.

So, What’s the Takeaway?

Free recall is one of the simplest learning tools you have… and one of the most scientifically validated. It doesn’t require equipment, software, or elaborate study rituals. It simply requires you to try remembering without looking.

It feels hard because it is hard. But the effort pays off.

When you regularly practice free recall (whether through writing summaries, closing your notes and explaining a concept aloud, or using digital flashcards) you transform memory from a passive storage system into an active, resilient network of knowledge.

Platforms like Brainscape reflect these principles, helping learners train their recall every time they study. And as research continues to show, the more you retrieve, the more you remember.

Get Brainscape's Educator User Guide

Curious to learn more about how to introduce Brainscape into your physical or virtual classroom? Our Educator User Guide provides a detailed walkthrough of how to get set up. It'll also give you all the material you need to motivate for its adoption amongst your students, their parents, and/or the faculty of your school or college:

Additional Reading (if you’re a sucker for punishment)

If you loved this article, you’ll also love these other nerdy science articles we wrote about:

- What is Spaced Repetition (& Why Is It Key To All Learning)?

- The “What the Hell" Effect & How to Conquer Its Vicious Cycle

- What Are Variable Rewards (& How Can Unpredictability Boost Your Motivation)?

For even more articles on how to harness cognitive science to improve learning, focus, and memory, check out our ‘Science of Studying’ hub.

References

Baddeley, A. D. (2000). The episodic buffer: A new component of working memory. Trends in Cognitive Sciences, 4(11), 417–423. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1364-6613(00)01538-2

Bjork, R. A. (2011). On the symbiosis of learning, remembering, and forgetting. In A. S. Benjamin (Ed.), Successful remembering and successful forgetting: a Festschrift in honor of Robert A. Bjork (pp. 1-22). London, UK: Psychology Press.

Carpenter, S. K., Pashler, H., & Vul, E. (2006). What types of learning are enhanced by a cued recall test? Psychonomic Bulletin & Review, 13(5), 826–830. https://doi.org/10.3758/BF03194004

Halamish, V. (2018). Pretesting effects and the role of collaborative learning. Educational Psychology Review, 30(4), 1127–1154. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10648-018-9446-y

Murdock, B. B. (1962). The serial position effect of free recall. Journal of Experimental Psychology, 64(5), 482–488. https://doi.org/10.1037/h0045106

Putnam, A. L., Sungkhasettee, V. W., & Roediger, H. L. (2016). Optimizing learning in college: Tips from cognitive psychology. Perspectives on Psychological Science, 11(5), 652–660. https://doi.org/10.1177/1745691616645770

Storm, B. C., Friedman, M. C., Murayama, K., & Bjork, E. L. (2021). Why testing enhances learning: Toward a unifying theory of retrieval practice. Psychonomic Bulletin & Review, 28(5), 1397–1413. https://doi.org/10.3758/s13423-021-01917-0

Tulving, E. (1962). Subjective organization in free recall of “unrelated” words. Psychological Review, 69(4), 344–354. https://doi.org/10.1037/h0043150

Wissman, K. T., Rawson, K. A., & Pyc, M. A. (2011). How and when do students use flashcards? Memory, 20(6), 568–579. https://doi.org/10.1080/09658211.2011.595723