This article is part of Brainscape's Science of Studying series.

Have you heard of the marshmallow experiment?

Researchers interviewed a bunch of toddlers kids, during which they gave them a marshmallow. But, the researchers explained, if the kids could resist eating the first marshmallow for a bit, they could have a second marshmallow!

In other words, if the kids could delay their gratification, they would get double the reward. Ultimately, the researcher’s goal was to test whether those who resisted would be better equipped for success even decades later, versus the toddlers who couldn't. Spoiler alert: they were. (Read the Stanford Marshmallow Experiment here.)

But doesn’t this sound familiar? Isn’t life just one big fat marshmallow experiment?

- Turn down drinks with friends tonight, so you can study and do well on your exam next week.

- Resist buying that new bag you want today, so you can save for that trip to Italy next year.

- Force yourself to go to the gym this morning, so you look good and maintain your health for the coming decades.

In every case, the reward is somewhere in the future, whether it’s next week, next year, or next decades. But the sacrifice of time, energy, and gratification is paid out in the present.

Some people are good at delaying gratification to secure longer-term rewards.

Most people, however, are not, which boils down to a term that only a scientist could find sexy—hyperbolic discounting.

If you identify with the latter group, you’re not lazy or impulsive. You’re human (and I’ll explain why in the next section). You’re also in exactly the right place to learn about the phenomenon that greedily craves instant gratification and how you can suppress it to improve your habits and decisions, irrespective of your goals.

So, if you’re ready to make smarter choices today for a richer tomorrow, let’s dive in…

What is Hyperbolic Discounting?

Hyperbolic discounting is the tendency to prefer a smaller reward NOW rather than a larger reward later, even when you know the later reward is better. In other words, a bigger payoff in the future gets discounted so steeply that your “future self” ends up with fewer tools, less stamina, and broken habits.

(Who hasn’t said “What the hell” and caved in to a temptation, rather than remain steadfastly on the straight and narrow path to one’s goals?)

The reason our brains are wired to do this is simple. Evolutionarily speaking, our brains haven’t quite caught up with our modern, abundant environment. To the primitive wiring inside your skull, a reward now should be instantly snatched up to ensure your survival.

No self-respecting Homo sapiens would ever walk past a beehive dripping with honey and think “I just ate two pounds of mammoth meat. I think I’ll save that honey for tomorrow.” No way! They’d put themselves into a food coma with that honey!

Why?

Because a cave bear might beat them to that honey between today and tomorrow, leaving them without that precious resource.

The same instinct to grab at rewards in the present has survived in our brains. The difference is that our survival isn’t at stake. Also, importantly, the rewards have changed… and not necessarily for the better.

Buying handbags, going out for drinks, and binging Netflix doesn’t improve our odds of survival… but it sure does feel good. And our brains perceive these indulgences as rewards.

Meanwhile, the real rewards worth going after—passing exams, travelling Italy, being healthy—are typically further away. Because of this, their perceived value plummets; so much so that watching an episode of your favorite TV show tonight literally feels like a bigger reward than passing your exam next week.

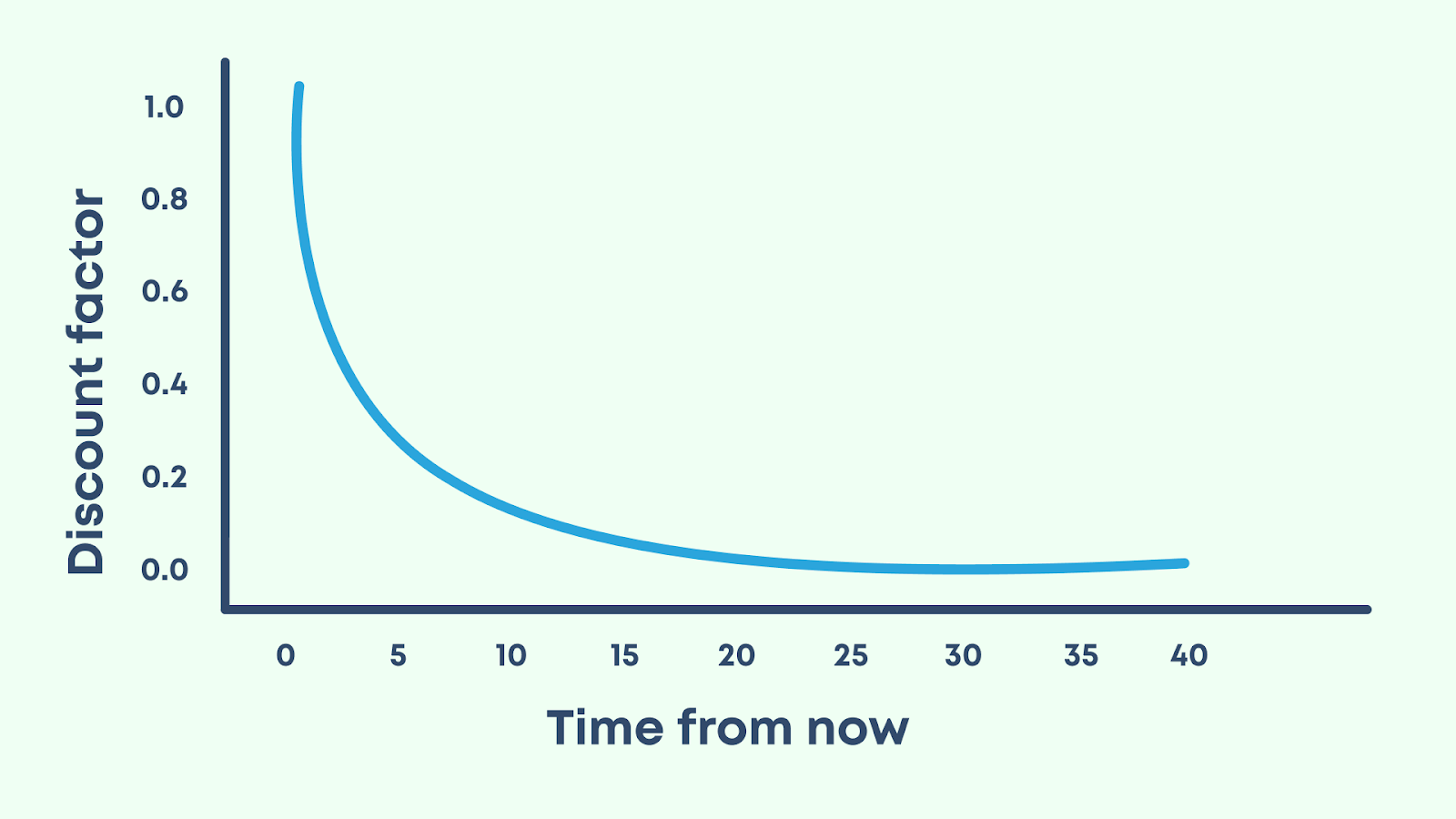

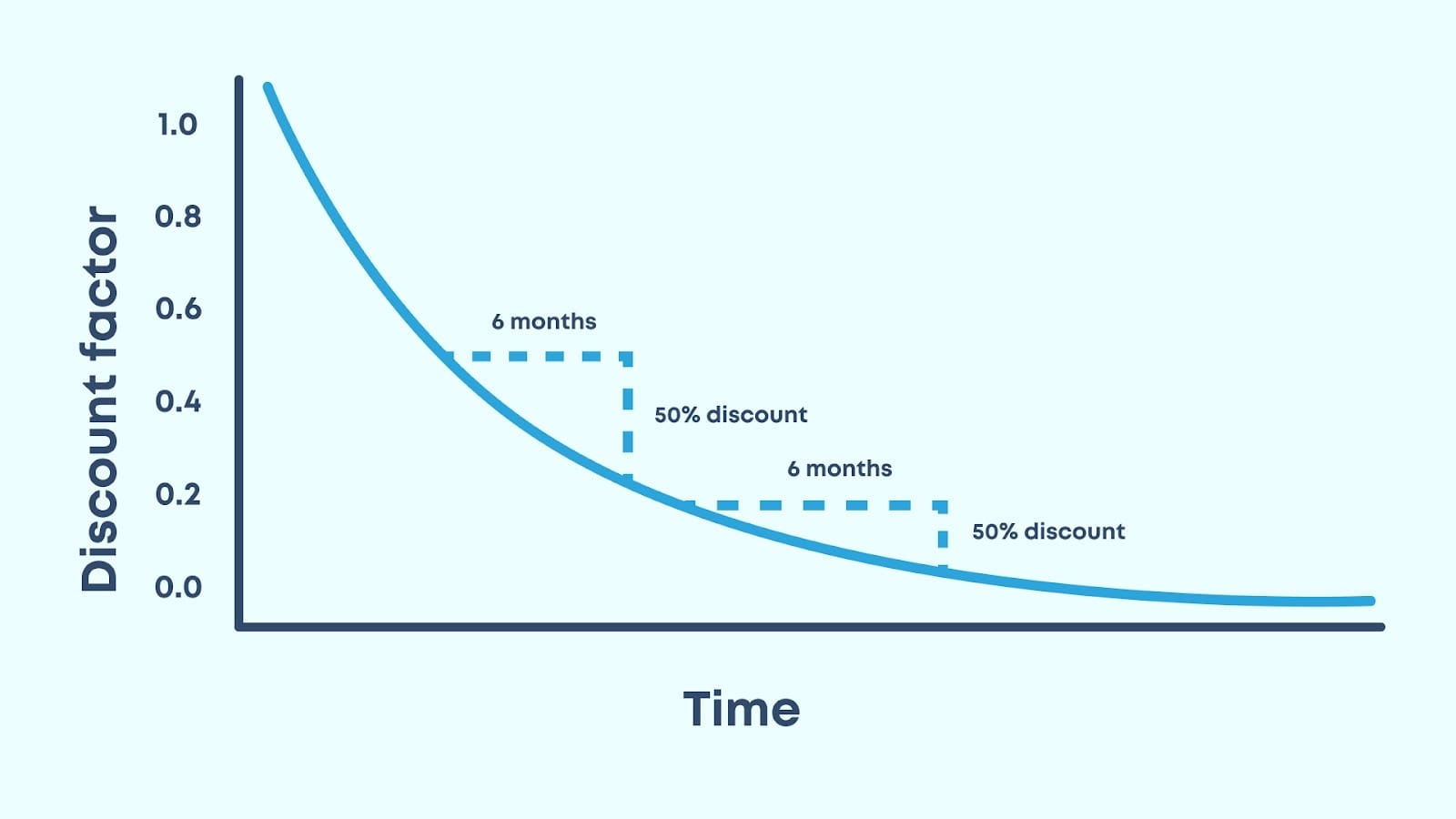

If you had to chart “perceived value over time distance from reward” on a Cartesian plane, it would form a hyperbola, hence the term “hyperbolic discounting”.

As a learner—whether you’re studying for college finals, upskilling with an advanced certification, or just trying to acquire a new language—hyperbolic discounting is one of those invisible forces sapping your progress.

Understanding it is your first step in outsmarting it.

How Does Hyperbolic Discounting Work, Cognitively?

As I explained with my caveman analogy, your brain isn’t wired for the distant future; it’s wired for now because 100,000 years ago, rewards provided by the environment were few and far between (and often fiercely contested). Survival meant leaping upon opportunities in the present, rather than putting them off for the future. This adaptation was essential for our survival back then. Today, however, it’s become maladaptive.

Here are the cognitive mechanics:

- Present bias: Your brain assigns a much higher value to rewards it can touch soon. The discounting curve is steep at the start, then flattens out.

- Intertemporal inconsistency: Because of hyperbolic discounting, you might plan one way when a goal is far away, then behave differently when the moment arrives.

- Cognitive load & attention: When you face a big delayed goal (learn advanced anatomy, master a language), it often demands heavy working-memory load and planning; but the immediate alternative (scroll social media, skip a session) is low-effort and high reward. Your brain opts for the easier path.

- Neural reward circuits: Immediate gratification triggers dopamine quickly; delayed gratification triggers more complex planning and less immediate reward signalling. And the neural difference makes waiting harder.

So while you might intend to study three hours this weekend, the pull of “one more episode” wins out because it’s nearer and easier, even though “future you” will regret it.

What Are the Key Principles of Hyperbolic Discounting?

Let’s break down the key levers you should recognize when hyperbolic discounting is in play. The goal of this exercise is simple. Becoming literate in how your brain is wired to think will empower you to intentionally reroute it towards smarter long-term decisions.

- Smaller-Sooner (SS) vs Larger-Later (LL) Rewards: The classic decision scenario. Example: “I’ll study 10 minutes now” (SS) vs “I’ll master a chapter next week” (LL).

- Delay Sensitivity: The longer you wait, the more your brain mentally reduces the value of the reward. The steeper the discount, the greater the present bias.

- Preference Reversal: What you plan to do when the goal is distant differs from what you do when the goal is near.

- Commitment Devices: Because of this bias, self-control often requires external structures (locks, deadlines, study groups) to keep your future self honest.

- Domain Spillover: Hyperbolic discounting affects ALL areas of your life: learning, finances, health, relationships… any domain where waiting matters. For example, one recent study found that those with steeper discounting curves showed more procrastination in academic tasks.

What Role Does Hyperbolic Discounting Play In Learning, Teaching, and Memory?

Hyperbolic discounting plays a big role in learning, teaching, and memory. YUGE. Because learning is, by its very nature, a game of delayed rewards. You don’t master anatomy in a weekend or become fluent in French after three Duolingo sessions. Real learning requires a long runway: you accumulate knowledge, practice it, forget some of it, revisit it, and gradually consolidate it over weeks, months, or even years.

Hyperbolic discounting stands in direct opposition to this process. So even though you know that today’s study session contributes to passing an exam or advancing in your career, your brain still whispers: “Wouldn’t it be nicer to skip this and watch something mindless instead?” Anyone trying to learn anything must constantly battle this pesky friction.

This preference for the “now” shows up everywhere in the learning process. Students often procrastinate or drop their study routines the moment life gets busy because the payoff—stronger mastery, better grades, professional readiness—feels far away, while the reward of not studying is instant.

Even memory encoding suffers: when you tell yourself you’ll “catch up later,” you end up relying on weaker, shallow study methods (like passively re-reading notes or watching video lectures) that compromise long-term retention.

This is a great moment to zoom out and check your study habits. The infographic below lays out the difference between passive studying that feels productive and the active strategies that actually move the needle.

compromise

For educators, the implication is clear. Teaching methods that build frequent, immediate feedback loops—like mini-quizzes, flashcards, low-stakes practice tests, peer checks—are a direct countermeasure to hyperbolic discounting. They turn learning into a series of short-term victories rather than one distant test at the end of the term or semester.

Ultimately, if your study system is structured around a big, far-off payoff without regular reinforcing checkpoints, you’re fighting your brain’s default wiring. And you’re probably losing. A smarter study system works with hyperbolic discounting by delivering steady, bite-size rewards that keep learners motivated all the way to the finish line.

And that brings me neatly to the perfect tool for the job…

How Do Digital Flashcards Fight Hyperbolic Discounting?

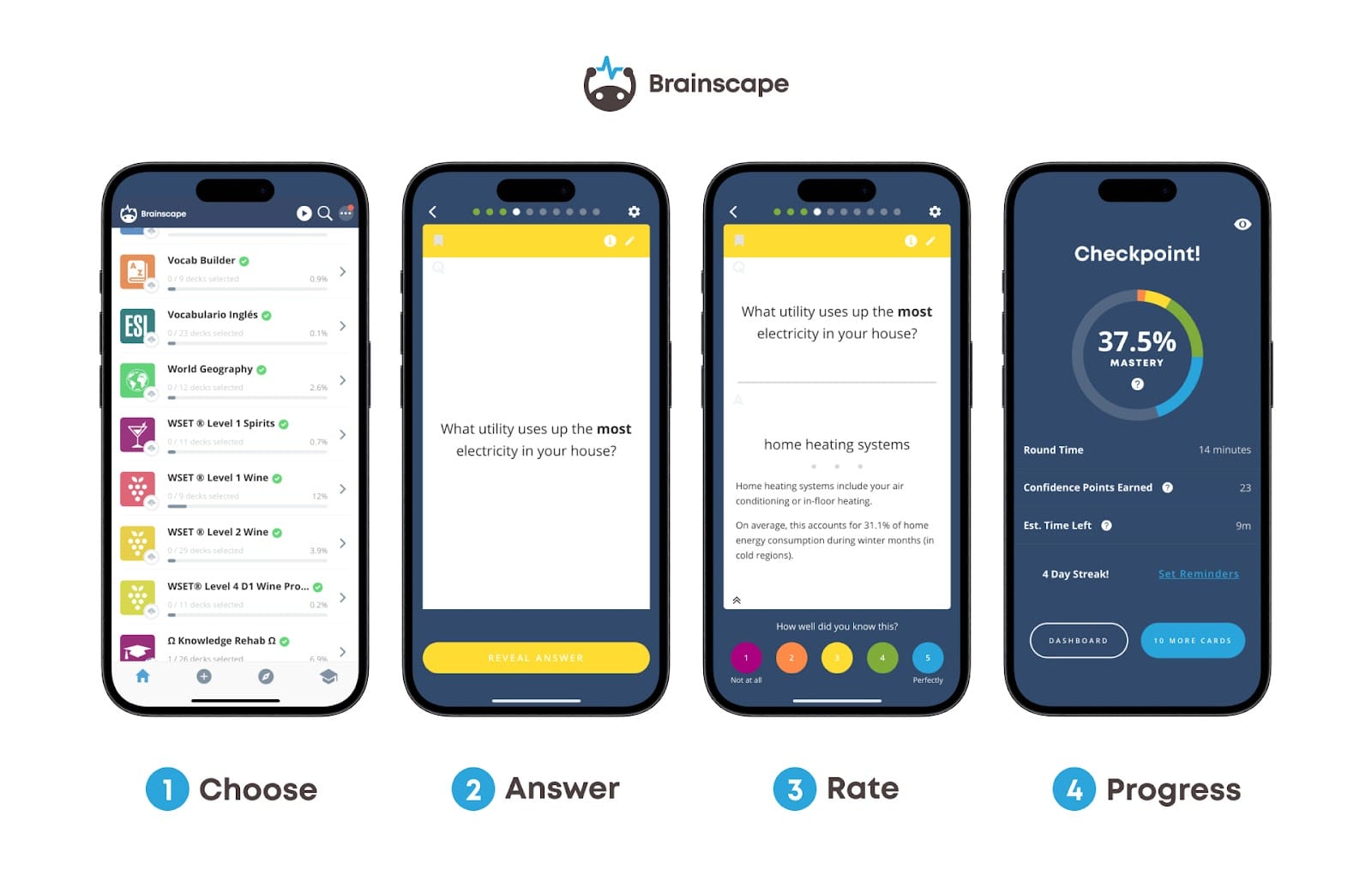

For many reasons, digital flashcards are the perfect tool for fighting hyperbolic discounting:

- They provide instant feedback: Each flashcard reveals whether you were right or wrong right away, making the reward immediate rather than delayed.

- They deliver learning in short, frequent sessions: Instead of sitting down to marathon, three-hour+ study sessions, you can whip open the app and study five minutes here, ten minutes there, making studying feel so much easier and more accessible, thereby reducing the temptation to procrastinate.

- They leverage adaptive spacing: Flashcard apps like Anki or Brainscape have study algorithms powered by confidence-based repetition, which resurfaces tough cards more often. So, you get repeated retrieval and reinforcement that only really even work if you are planning ahead, rather than cramming at the last minute.

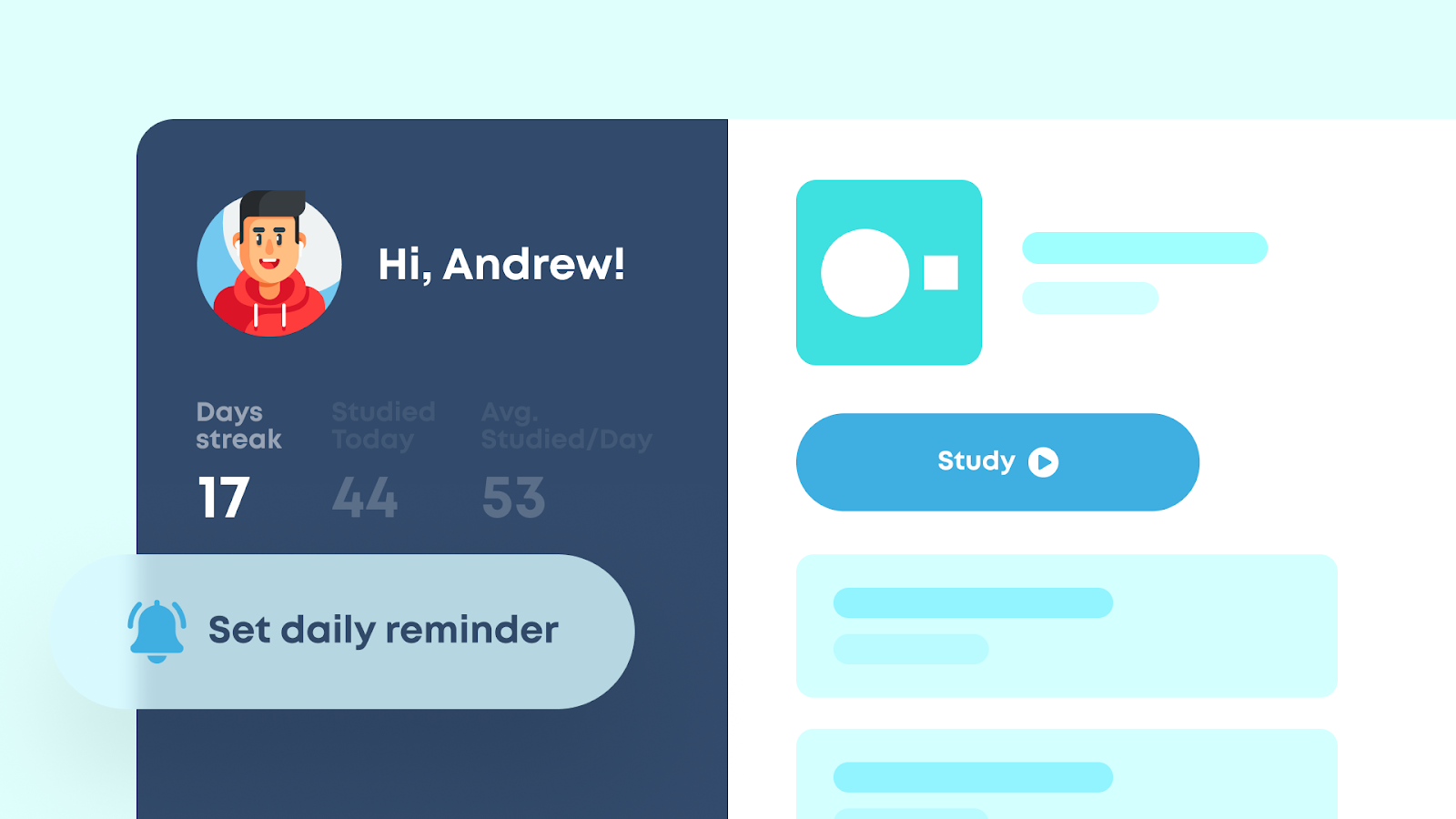

- They make your progress visible: Many flashcard apps also show study streaks, mastery levels, and progress metrics, offering near-term gratification which aligns with our bias toward the present.

So, while hyperbolic discounting tempts you to give up on the big goal because “it’s too far away,” flashcards convert your study path into many near-term wins. Platforms like Brainscape use these principles to keep you motivated and engaged, working with your brain’s wiring rather than against it.

What’s the Difference Between Hyperbolic and Exponential Discounting?

If you’ve done what I’ve done and gone down a rabbit hole on the literature on hyperbolic discounting, you’ll quickly realize that it has a nasty, redneck cousin: exponential discounting.

Hyperbolic and exponential discounting both describe how we value rewards over time, but they differ in how consistently we treat the future. Exponential discounting assumes a steady, rational decline in value: a reward that’s one month away is always discounted at the same rate, no matter when you evaluate it. It reflects the behaviour of a perfectly consistent decision-maker, which is more the exception than the rule.

Hyperbolic discounting, on the other hand, captures how real humans actually behave. Instead of a steady decline, the perceived value of a reward drops sharply as it moves just slightly into the future, then flattens out. This creates time inconsistency: a study session tomorrow feels worthwhile today (which is why we tend to be a little more ambitious with our future plans), but when tomorrow becomes “right now,” the immediate reward of not studying suddenly wins.

In short, exponential discounting describes ideal planning; hyperbolic discounting describes why we procrastinate, abandon routines, and struggle to prioritize long-term goals, even when we logically know better.

So, What’s the Takeaway?

Hyperbolic discounting is a powerful explanation for why we start great plans and then stall. It shows why your future-oriented goals (learn Spanish, ace this exam, save that money) often face sabotage… not from lack of effort, but from timing bias.

To overcome hyperbolic discounting, you should:

- Build immediate reward mechanisms into your study routine (mini-tests, flashcard wins, visible progress).

- Break long-term goals into short chunks, each with its own near-term payoff.

- Use commitment devices like study buddies, scheduled reviews, and public promises to keep your future self honest.

- Recognise that delayed rewards alone won’t beat your brain’s shortcut to “just this once”, which is why you need to game the system with smaller, more immediate wins.

So, stop fighting your brain.

Work with it.

And now you have the tools and advice to do that!

Get Brainscape's Educator User Guide

Curious to learn more about how to introduce Brainscape into your physical or virtual classroom? Our Educator User Guide provides a detailed walkthrough of how to get set up. It'll also give you all the material you need to motivate for its adoption amongst your students, their parents, and/or the faculty of your school or college:

Additional Reading (if you’re a sucker for punishment)

If you loved this article, you’ll also love these other nerdy science articles we wrote about:

- What is Cognitive Load Theory? (& Why Does Too Much Info Hurt Learning)

- The “What the Hell" Effect & How to Conquer Its Vicious Cycle

- What is Spaced Repetition (& Why Is It Key To All Learning)?

For even more articles on how to harness cognitive science to improve learning, focus, and memory, check out our ‘Science of Studying’ hub.

References

Ainslie, G. (2012). Pure hyperbolic discount curves predict “eyes open” self-control. Theory and Decision, 73(3), 297-323. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11238-011-9272-5

Cruz Rambaud, S., Hernandez-Perez, J. (2023). A naive justification of hyperbolic discounting from mental algebraic operations and functional analysis. Quantitative Finance and Economics, 7(3), 463-474. https://doi.org/10.3934/QFE.2023023

Duckworth, A. L., & Seligman, M. E. P. (2005). Self-Discipline Outdoes IQ in Predicting Academic Performance of Adolescents. Psychological Science, 16(12), 939–944. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-9280.2005.01641.x

Enke, B., Graeber, T., Oprea, R. (2023). Complexity and hyperbolic discounting. NBER Working Paper w31047. https://www.nber.org/papers/w31047

Frederick, S., Loewenstein, G., & O’Donoghue, T. (2002). Time Discounting and Time Preference: A Critical Review. Journal of Economic Literature, 40(2), 351–401.https://doi.org/10.1257/002205102320161311

Laibson, D. (1997). Golden eggs and hyperbolic discounting. Quarterly Journal of Economics, 112(2), 443-477. https://doi.org/10.1162/003355397555253

Mazur, J. E. (1987). An Adjusting Procedure for Studying Delayed Reinforcement.In M.L. Commons et al. (Eds.), Quantitative Analyses of Behavior: Vol. 5. The Effect of Delay and of Intervening Events on Reinforcement Value (pp. 55–73).