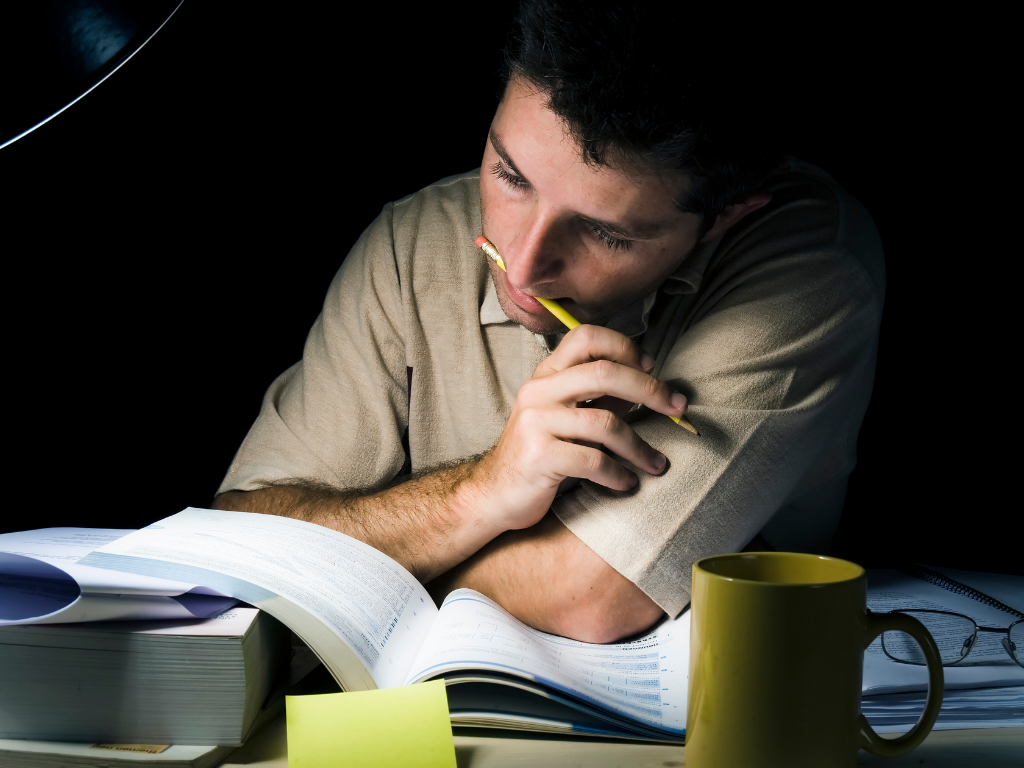

MCAT psychology and sociology (also known as psych/soc) is an oddly paradoxical beast. A lot of students think psych/soc will be a breeze and yet discover it to be the hardest science section to study for.

Why is studying for MCAT psychology and sociology so intimidating?

A surface-level answer might be “because there are just so many psych terms.” This is true, but the same could be said about biology, biochemistry, or any other science subject. A better answer is that far more ambiguity exists regarding which psych terms are MCAT-relevant.

I could go on about potential reasons for this all day, but the end result is that we often don’t feel confident that some random psychologist’s name or some diagnostic criterion for a psych disorder that definitely won’t be tested.

Contrast this with biochemistry, where even though there are around 1,300 enzymes in the human body, we know that hexokinase is likely to appear on the MCAT, whereas we never in a million years would need to know details about, say, leukotriene C4 synthase.

With that said, let’s address some MCAT tips on psych/soc to help you take on this notoriously tricksy section ...

What Are Some Tips On Tackling The MCAT Psych/Soc Section?

The Association of American Medical Colleges (AAMC) outline is a resource published by the test-makers themselves that provides a tremendous and often underutilized amount of helpful MCAT info. Now, the outline was never meant to serve as a comprehensive guide to every fact or individual term you need to know for the exam. But while that’s true across all of the science sections, the outline for MCAT psychology and sociology has a much less decisive feel than the other parts.

Take the use of “e.g.,” which basically means “for example.” On the chemistry/physics part of the outline, you might see something like “Strong acids and bases (e.g., nitric, sulfuric),” and this means there are likely other, unspecified strong acids you need to know. (This is true, by the way: there are actually seven strong acids that you should be familiar with for the exam.)

In the chemistry/physics and biology/biochemistry sections combined, the AAMC uses “e.g.” a total of 11 times. In the MCAT psychology/sociology outline, however, it’s used 39 times. And in contrast to the strong acid example, where most MCAT students quickly learn what the other strong acids are, we might have no clue how far to look for those unlisted examples in psych/soc.

Take this line: “Heuristics and biases (e.g., overconfidence, belief perseverance).” There are so many more biases that exist and dozens of named heuristics, but we’re left on our own to discern which ones are important and which are not.

I say all of this to emphasize the following immutable fact: ambiguity in psych/soc is part of MCAT life! If you buy a psych/soc book from every MCAT company, you’re going to see some terms in one book that aren’t in the rest. When you take full-length MCAT practice tests, you’re going to see a few MCAT psychology and sociology terms that you’ve never encountered. It’s just going to happen.

For the sake of your mental health, I recommend ridding yourself of the notion that some complete list of all MCAT-relevant psych terms exists: it doesn’t! But that doesn’t mean we’re helpless; not by a long shot. Let’s talk about how to cope with this uncertainty, which I’ve broken into three stages:

- While you’re studying,

- While you’re reviewing practice materials and full-length practice exams, and

- While you’re taking the actual MCAT.

Let’s take a closer look at each.

MCAT Tip 1: Coping With MCAT Psych/Soc Uncertainty While You’re Studying

While studying, the best way to become comfortable with uncertainty is to gain a sense of what kinds of things the AAMC likes to test. Most good MCAT prep books have been designed and (especially) revised in accordance with AAMC trends over time, so avoiding sources that haven’t been subjected to this process is generally helpful.

As examples of “what the AAMC likes to test,” theories are generally tested far more than the names of psychologists. You might be asked about Mead’s theory of the “I” and the “me,” but you likely won’t be asked which psychologist pioneered symbolic interactionism (which is actually also Mead).

Similarly, the AAMC loves experimental design in psych/soc, so I highly recommend trying to understand everything you encounter about types of study design, variables, survey methods, and so on.

MCAT Tip 2: Coping With Uncertainty While You’re Reviewing MCAT Practice Test Questions

The next part of handling uncertainty in MCAT psychology and sociology happens when reviewing practice passages or full-length MCAT practice exams. In the answer choices, you are going to see terms you don’t know, and those terms might not be in the MCAT prep book you’re using or in any MCAT content video.

Broadly, I recommend keeping a notebook where you write down each unfamiliar psych/soc concept as it arises. (To reiterate, I’m referring to concepts in the answer choices—not ones that are introduced and described in the passage itself.)

Below each entry, keep some space free, so if you see that concept again, you can add to your growing knowledge of it, and don’t just add facts and definitions, but information about the context that term was tested in, too.

By the time your exam date rolls around, you’ll see some entries that are full of notes, and others where you never saw that term again after the first time, as evidenced by a bunch of blank space. This can serve as an extremely helpful guide of what you should spend more time reviewing versus less.

One caveat, though!

The process of documenting unfamiliar terms can’t be done mindlessly, because not all unfamiliar terms are created equal. For instance, say choice D for a particular question is a term that you’ve never seen in your life, but enough context was given in the passage to discern that it was wrong. This is evidence of a passage reasoning issue, not a content one, so don’t go out and try to learn all about what D is.

Similarly, unfamiliar terms that you see within correct answers tend to be more important than those in wrong answers, because perhaps the correct answer was so obviously right that you were never expected to know the meaning of the wrong choice anyway. Maybe the wrong answer wasn’t even a real term, although this is unlikely.

All of this is true for both AAMC and third-party materials, although to be safe, I do recommend at least documenting every wrong-answer term you see in your AAMC practice, even if the right answer was clear.

Along similar lines, if your test date is approaching and you have available materials left, like say a couple of full-length MCAT practice tests you’ll never have time to take, go through at least the psych/soc sections of those tests and see if any unfamiliar terms or concepts come up.

This is particularly true of AAMC materials; if you won’t get to a part of the psych/soc Section Bank, still make sure you review it carefully and with this same critical discernment, to make sure you understand all concepts that came up that weren’t explained in context.

MCAT Tip 3: Coping With MCAT Psychology And Sociology Uncertainty During The Test!

Finally, when you reach your exam date, note that no matter how much preparation you’ve done, you’re still quite likely to see a term or two that you’ve never heard of in your life. My best advice here is: don’t panic.

Check the passage and question first—is there any information there that can answer the question for you? If not, try to break down the names of the terms; see if they relate to any concepts you are familiar with.

And finally, even if you have to take a wild guess, remember that some questions in every MCAT section are unscored field test questions, used to evaluate student responses for potential future MCAT use. And maybe no one else knew that weird term either, so the question failed its field test, but it didn’t impact your score at all.

Why Are Digital Flashcards The Best Study Tool?

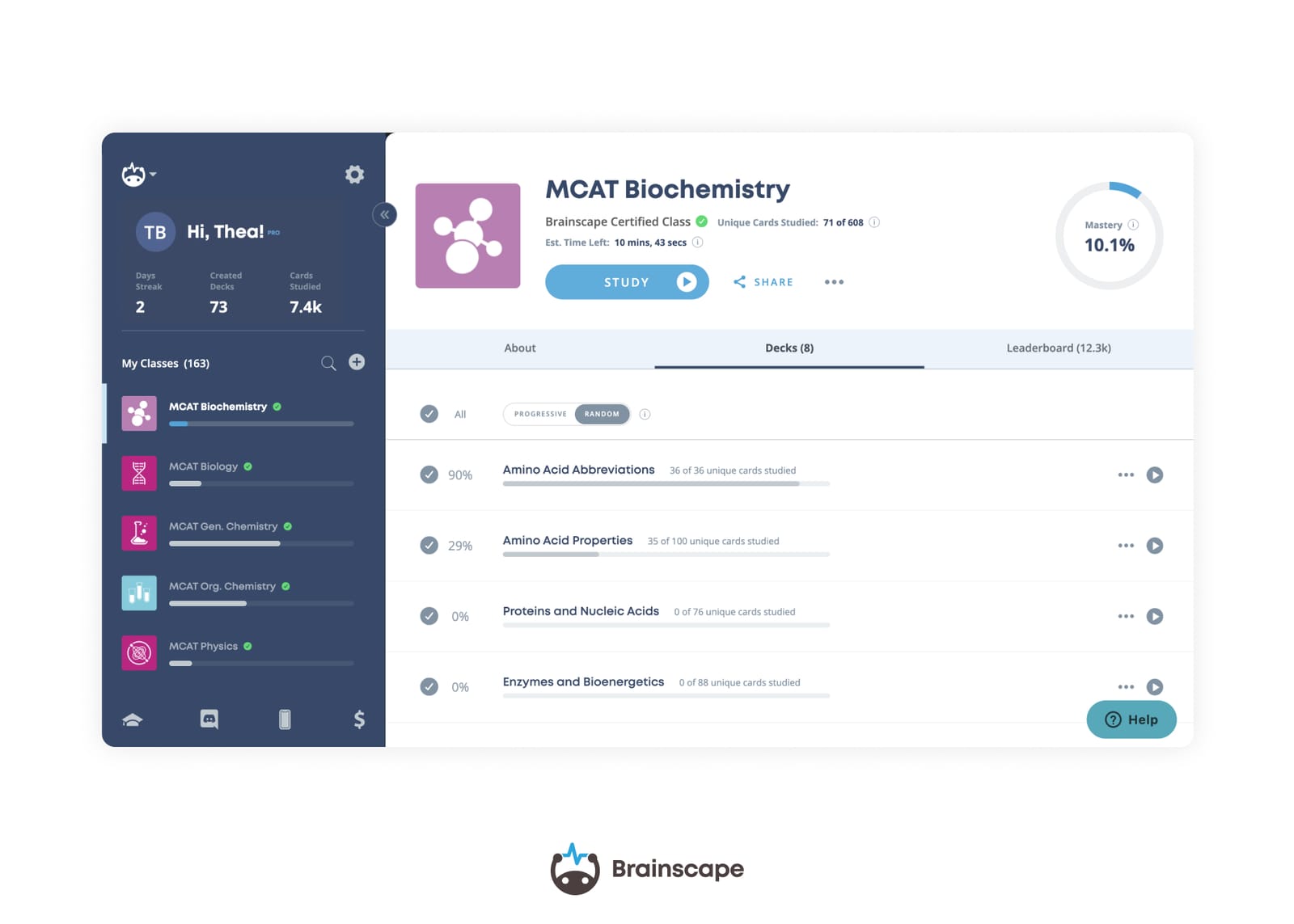

Before we sign off, we want to add an incredibly powerful study tool to your arsenal of intellectual weaponry against the MCAT, and not just its psych/soc section, but all FOUR MCAT sections.

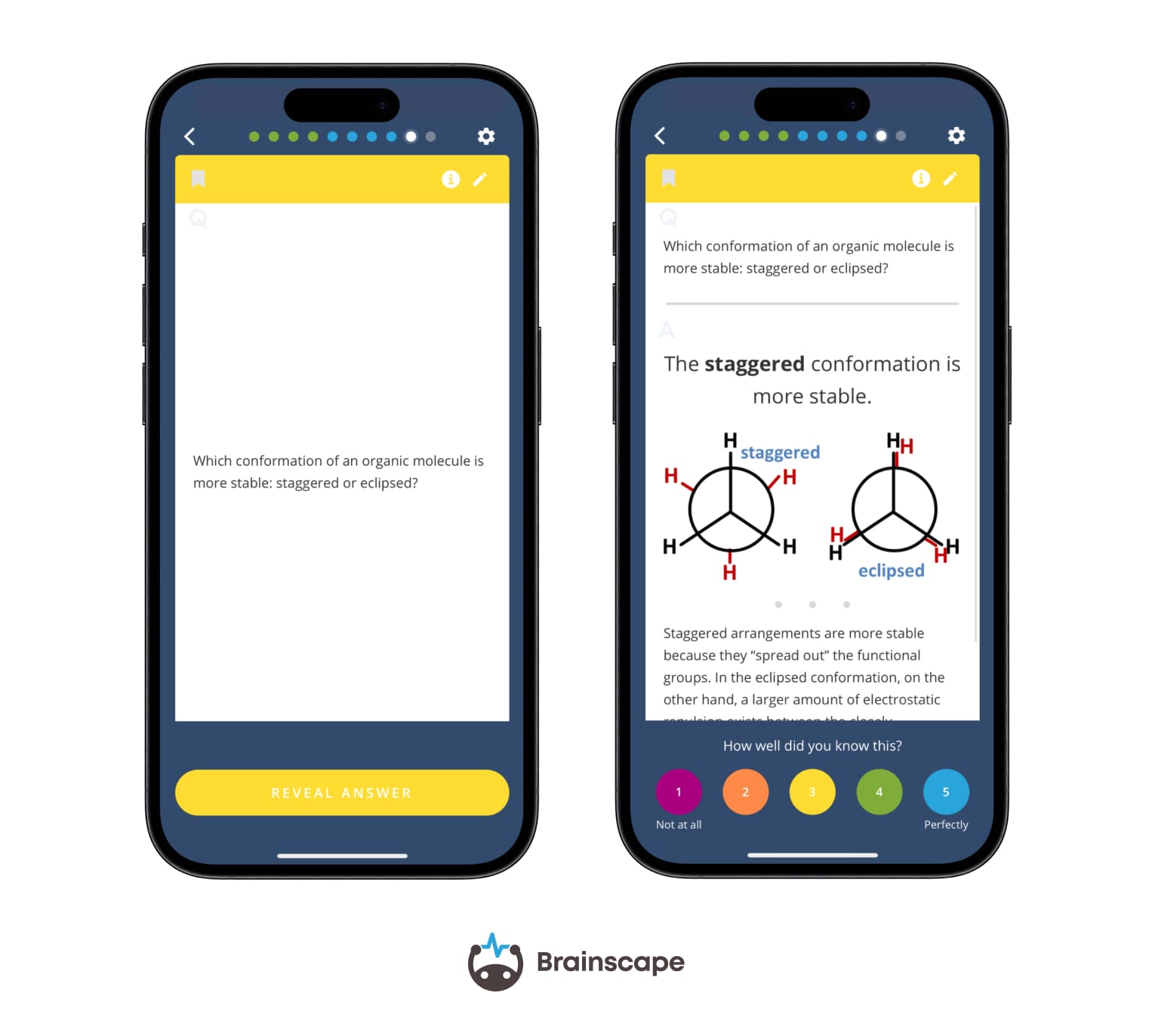

Meet digital flashcards, a tool that helps you memorize information twice as efficiently as traditional study methods.

You might be thinking: Twice as fast? How? Here's the cognitive science. Flashcards rely on a study approach called spaced repetition. Because the brain forgets roughly half of new information within a single day, you can only retain it by revisiting the material several times. That means circling back to concepts repeatedly, right as they’re about to fade from memory.

Modern digital flashcard apps like Brainscape or Mochi take care of this automatically by organizing what you’re learning and reintroducing it at the right moment for your individual pace. These adaptive tools have been shown to help medical students study far more efficiently. The advantages go beyond medical school and remain relevant in clinical practice. In fact, one study showed that spaced repetition helped working clinicians reduce the time needed to meet blood pressure targets for their hypertensive patients.

Another advantage is that flashcards promote active recall, which means drawing knowledge from your memory instead of simply recognizing it on a page. Even if you don’t get the answer right, the act of attempting recall followed by instant feedback makes future reviews more productive.

Flashcards also enhance metacognition, or the ability to judge how well you know a topic. By quickly rating your confidence after each card, you gain awareness of your strengths and weaknesses, which results in improved memory outcomes.

Studies specifically conducted on medical students have shown that those using spaced repetition doubled their test scores compared to a control group after just 29 days. So if you’re aiming to make your study time twice as efficient and improve your MCAT score, digital flashcard platforms like Brainscape or Anki are an unbeatable tool for memorization in med school.

A Final Note On MCAT Psychology And Sociology

In the absence of a complete list of all MCAT-relevant psych terms and the ambiguity of the AAMC’s outline for MCAT psych/soc, many students approach this section of the exam with great uncertainty. And with the MCAT being the gatekeeper to medical school, this uncertainty can metastasize into terrible anxiety.

However, armed with the MCAT tips provided by expert Clara Gillan in this guide and a powerful digital flashcard app, you should have everything you need to approach this section with confidence!

Additional Reading

- The Ultimate 3 Month MCAT Study Plan

- Should Pre-Med Students Fear Organic Chemistry?

- Dropping A Course (Especially A Premed Course!): Is It Ever The Right Decision?

References

Deng, F., Gluckstein, J. A., & Larsen, D. P. (2015). Student-directed retrieval practice is a predictor of medical licensing examination performance. Perspectives on Medical Education, 4(6), 308–313. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40037-015-0220-x

Dobson, J. L. (2012). Effect of uniform versus expanding retrieval practice on the recall of physiology information. Advances in Physiology Education, 36(1), 6–12. https://doi.org/10.1152/advan.00090.2011

Ebbinghaus, H. (1913). Memory: A contribution to experimental psychology. New York: Teachers College, Columbia University.

Karpicke, J. D. (2012). Retrieval-based learning: Active retrieval promotes meaningful learning. Current Directions in Psychological Science, 21(3), 157-163.

Kerfoot, B. P. (2010). Adaptive spaced education improves learning efficiency: A randomized controlled trial. Journal of Urology, 183(2), 678–681. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.juro.2009.10.005

Kerfoot, B. P., Turchin, A., Breydo, E., Gagnon, D., & Conlin, P. R. (2014). An online spaced-education game among clinicians improves their patients’ time to blood pressure control. Circulation: Cardiovascular Quality and Outcomes, 7(3), 468–474. https://doi.org/10.1161/circoutcomes.113.000814

Kornell, N., Hays, M. J., & Bjork, R. A. (2009). Unsuccessful retrieval attempts enhance subsequent learning. Journal of Experimental Psychology: Learning, Memory, and Cognition, 35(4), 989–998. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0015729

Sadler, P., & Good, E. (2006). The impact of self- and peer-grading on student learning. Educational Assessment, 11(1), 1–31. https://doi.org/10.1207/s15326977ea1101_1