This article is part of Brainscape's Science of Studying series.

Picture a construction site: workers climbing ladders, beams rising skyward, a temporary metal structure supporting a building as it grows.

That structure, the scaffold, isn’t the building itself. It’s what allows the builders to reach new heights safely, piece by piece, until the structure can stand on its own.

Now replace the building with your brain.

That’s scaffolding in education!

In simple terms, scaffolding is a teaching and learning technique in which an instructor (or tool) provides temporary supports that help learners reach a higher level of understanding than they could achieve on their own. As the learner becomes more capable, those supports are gradually removed.

What’s the goal of scaffolding? To help students tackle challenges that would otherwise be just out of reach, until they can confidently stand (and think) on their own. This matters a whole lot to you if you care about learning and personal growth, whether it’s your own or that of a class of students.

So, let’s take a romp through the science of scaffolding and how you can harness it to help you (or your students) learn so much more efficiently!

Where Did the Idea of Scaffolding Come From?

Scaffolding is rooted in the work of Russian psychologist Lev Vygotsky (1896–1934), who proposed that learning happens most effectively within a certain “zone”, which he called (brace yourselves), the Zone of Proximal Development or ZPD for short. The ZPD is where a learner is challenged just enough to grow, but not so much that they shut down.

Years later, Jerome Bruner, David Wood, and Gail Ross brought the metaphor to life. Their famous 1976 study, The role of tutoring in problem solving, described how tutors support children solving problems by:

- Simplifying complex tasks,

- Maintaining focus on key goals,

- Providing feedback, and

- Gradually transferring responsibility to the learner.

Their insight: The right kind of temporary help can lead to permanent understanding.

This makes sense, right? Think about that time a friend taught you how to play a new board game: by gradually explaining things as you went along and helping you make decisions until you no longer needed their input on strategy. That’s the general idea.

How Does Scaffolding Work in Practice?

Think of scaffolding as a dynamic learning partnership between student and teacher (or learner and tool). A good teacher doesn’t just dump information and walk away; they adjust their support as the learner progresses.

Let’s say you’re learning about cell biology, specifically, how photosynthesis works. Without scaffolding, it’s easy to become overwhelmed with too many details too soon: light-dependent reactions, ATP synthase, Calvin cycles, carbon fixation, enzymes, chloroplast anatomy...

I mean, holy crap, are we still talking about plants?

Instead, here’s how a teacher might scaffold that learning journey in a way that helps you learn so much more efficiently:

Step 1: Start with the big picture.

Begin by linking to prior knowledge, for example, a discussion about how plants and humans both need energy to survive. This helps students see the why before diving into the how.

Step 2: Model the process.

Next, the teacher might walk through a simplified diagram of photosynthesis, narrating how light energy turns into chemical energy. They might literally think aloud, explaining each step’s role:“Here’s where sunlight hits the chlorophyll… which excites electrons… and starts the energy transfer chain.”

Modeling makes the invisible visible.

Step 3: Chunk and guide practice.

Once students grasp the overall process, the teacher breaks it down further. One class might focus only on the light-dependent reactions, another on the Calvin cycle. Students practice labeling diagrams, answering guided questions, making flashcards, or completing sentence stems like: “The purpose of the light-dependent reactions is to…”

These structured prompts are temporary supports. They guide thinking until students can explain it themselves.

Step 4: Prompt with questions.

As learners gain confidence, the teacher steps back, asking probing questions instead of giving explanations:

“What happens to the ATP after it’s produced?”

“Why does the Calvin cycle depend on the light-dependent reactions?”

The goal shifts from remembering to connecting concepts.

Step 5: Fade the support.

Finally, the scaffolds are removed. The training wheels are off! Students might draw or explain the entire process from memory, or apply it to new contexts, such as by predicting what happens to photosynthesis in low-light conditions.

In every step, the teacher’s role changes: from coach to consultant, from guide to observer.And the student’s role transforms, too: from recipient of knowledge to constructor of understanding.

When done right, scaffolding doesn’t just teach what photosynthesis is; it teaches students how to learn biology itself.

Are you now starting to get why scaffolding is such a pivotal concept in education?

Why Does Scaffolding Matter for Learning?

Scaffolding matters in education because learners don’t absorb knowledge in one gulp. They construct it, piece by piece. And without proper structure, that construction can collapse under its own weight.

Research shows that scaffolding:

- Improves the retention and transfer of knowledge,

- Bolsters a student’s confidence that they can succeed, and

- Encourages metacognition, which is the awareness of one’s own learning process (Hmelo-Silver et al., 2007, Educational Psychologist).

In the absence of scaffolding, learners experience frustration or disengagement. You’re either overwhelmed by too much complexity or bored by oversimplification, both of which are notorious motivation assassins.

In contrast, well-scaffolded learning keeps students in that productive struggle zone, where they’re challenged just enough to feel progress.

That’s the zone of proximal development. The sweet spot where real learning happens.

What Are Some Common Scaffolding Strategies?

The question now is, how can you integrate scaffolding into your own learning (or your classroom, if you’re an educator)? Here are a few tried-and-true scaffolding methods:

- Pre-teaching vocabulary or background info. Before you dive into a complex subject area, familiarize yourself with the vocabulary and context. The idea here isn’t to deeply internalize the content but rather to briefly introduce your brain to the underlying words and story. This reduces cognitive load and sets context.

- Guided questioning. Start answering questions on the topic, beginning with simple questions and then getting increasingly complex. This helps you think critically without giving away answers. (Flashcards are a great way to accomplish this by the way. More on that in a bit.)

- Graphic organizers. Visually map complex ideas by drawing timelines, concept maps, or cause-effect charts. This helps your brain connect the dot between isolated concepts, thereby building a more complete, “whole picture” understanding of the subject as you continue to add new concepts into your existing map.

- Think-aloud modeling. The teacher verbalizes their thinking process, giving students a cognitive “template” to imitate. You could do this yourself by speaking aloud your understanding of the subject, explaining it from the basics up. (There’s actually a name for this: the Feynman Technique, named after the famous physicist.)

- Worked examples. Start by first studying examples before attempting similar tasks independently. Work through a problem set with the help of a friend, teacher, or by following along in the workbook. Then, once you understand the methodology, attempt it yourself.

- Flashcards and retrieval practice tools. Being prompted to answer questions on something you’re learning (beginning with simple concepts and steadily progressing to more complex concepts) is a powerful way to actively engage with a subject, which deepens learning faster.

Scaffolding is easier to apply when students can name what they’re currently doing, and what to swap in next. The infographic below gives a quick, classroom-friendly way to spot passive habits and replace them with active strategies that build independent learning.

Actually, let’s look a little closer at flashcards, specifically digital flashcards, because they are one of the easiest, yet most powerful tools for scaffolding learning…

How Do Digital Flashcards Leverage Scaffolding?

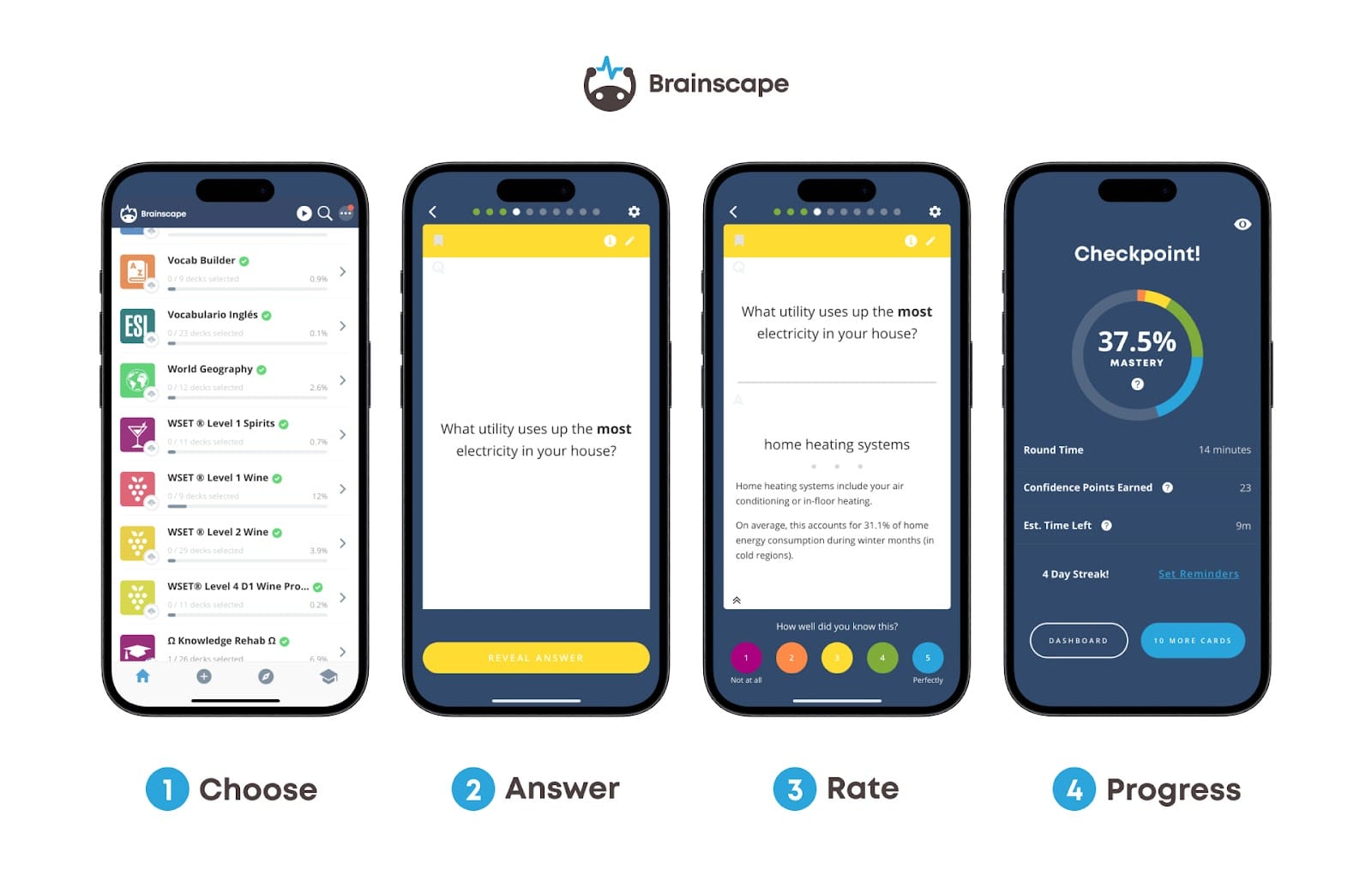

Digital flashcards (like Brainscape, pictured above) are a deceptively simple form of scaffolding. They break complex subjects into bite-sized, repeatable question-and-answer pairs, allowing you to build your knowledge layer by layer.

For example, in biology, instead of trying to memorize an entire chapter on cell respiration in one go, you might start with flashcards that isolate each component:

- “What is the role of ATP in energy transfer?”

- “Where does glycolysis occur?”

- “What is the difference between aerobic and anaerobic respiration?”

Each question targets a single “brick” of understanding. Repeated practice strengthens recall of those individual bricks until you can confidently connect them into larger conceptual structures, the same way scaffolding supports a building until it’s self-sustaining.

When combined with retrieval practice (the act of recalling information from memory rather than rereading it), flashcards naturally fade their own support: as you master easier questions, you spend more time on the challenging ones.

Over time, this self-adjusting process mirrors the scaffolding cycle: support → practice → independence (Faber et al., 2024).

In summary, digital flashcards use scaffolding principles in three powerful ways:

- Each flashcard isolates a single concept, preventing cognitive overload. You’re essentially “building” knowledge layer by layer — just like a teacher scaffolding lessons in the right sequence.

- They then automate your progression: Flashcard apps like Brainscape automatically adjust which cards you see and when, ensuring that you review harder concepts more frequently, while fading out the ones you’ve mastered (a learning strategy called spaced repetition).

- And they encourage you to engage your powers of active recall. By asking you to retrieve knowledge from memory (rather than reread it), digital flashcards strengthen your understanding through productive struggle, a key component of effective scaffolding.

A Final Word on Scaffolding in Education

Scaffolding is fundamentally about giving learners the temporary structure they need to eventually stand on their own. When teachers scaffold instruction, or when learners use tools that scaffold their studying, they’re applying one of the most powerful learning principles in education: helping the brain bridge the gap between knowing nothing and knowing enough to learn independently.

And once that scaffold comes down, what remains is a sturdy structure of understanding: one that the learner (that’s YOU) built themselves!

Get Brainscape's Educator User Guide

Curious to learn more about how to introduce Brainscape into your physical or virtual classroom? Our Educator User Guide provides a detailed walkthrough of how to get set up. It'll also give you all the material you need to motivate for its adoption amongst your students, their parents, and/or the faculty of your school or college:

Additional Reading

Don’t stop here! Keep nerding out over how your brain actually works with these awesome reads:

- What is Hyperbolic Discounting (& Why Is It Keeping You From Your Goals)?

- What Are Variable Rewards (& How Can Unpredictability Boost Your Motivation)?

- The Science of Social Motivation: Why We Work Harder When People Are Watching

For even more articles on how to harness cognitive science to improve learning, focus, and memory, check out our ‘Science of Studying’ hub.

References

- Bruner, J. S. (1978). The Role of Dialogue in Language Acquisition.

- Faber, T. J. E., et al. (2024). Effects of adaptive scaffolding on performance, self-regulation, and cognitive load in a medical emergency simulation. BMC Medical Education.

- Hmelo-Silver, C. E., Duncan, R. G., & Chinn, C. A. (2007). Scaffolding and Achievement in Problem-Based and Inquiry Learning: A Response to Kirschner, Sweller, and Clark (2006). Educational Psychologist, 42(2), 99–107.

- Magnusson, C. G., Luoto, J. M., & Blikstad-Balas, M. (2023). Developing teachers’ literacy scaffolding practices—Successes and challenges in a video-based longitudinal professional development intervention. Teaching and Teacher Education, 132, 104274.

- Vygotsky, L. S. (1978). Mind in Society: The Development of Higher Psychological Processes. Harvard University Press.

- Wood, D., Bruner, J. S., & Ross, G. (1976). The Role of Tutoring in Problem Solving. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 17(2), 89–100.

- American Psychological Association: https://www.apa.org/education-career/undergrad/scaffolding