Every educator knows the pattern.

Students swear they’ll study earlier next time. They mean it. They even try… briefly. Then the exam looms, panic sets in, and out comes the cram session.

The problem usually isn’t laziness. It’s human psychology.

Students are operating with the same brain wiring as the rest of us: biased toward urgency, short-term rewards, and delayed consequences. Knowing how to study rarely changes behavior on its own.

To get students to actually study regularly, educators need to combine cognitive science with behavior design.

Here’s how to work with your students’ brains so that they learn to study regularly (and learn to prefer it)!

Why Do Students Keep Cramming Even When They Know It Doesn’t Work?

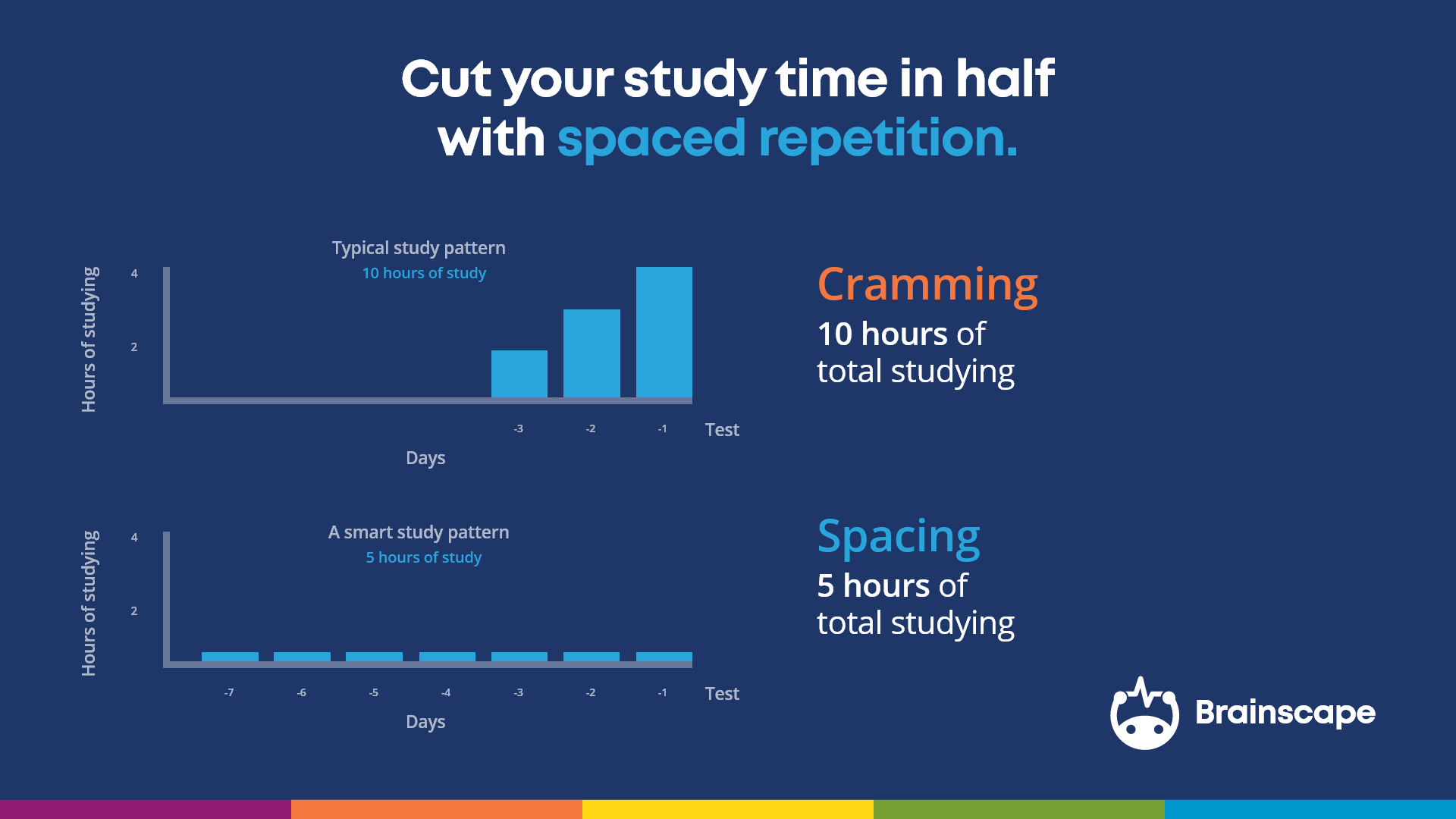

Cognitive science has been crystal clear for decades: spaced repetition beats cramming for long-term retention (Cepeda et al., 2009).

So why don’t students do it?

Because studying feels hard, and it takes a real sense of urgency to overcome the natural inertia that arises when you need to do something you don’t want to do!

This is a pretty common psychological phenomenon called hyperbolic discounting, which is disproportionately valuing small but immediate rewards (not studying) over larger, later rewards (acing a test).

So, when does that urgency kick in?

Usually, a couple of days before the test or exam, at which point the student becomes panicky with the amount of work they need to get through. So, they sit down to a few marathon study sessions; perhaps even pulling an all-nighter to cram everything they can.

The thing is, the brain can only cope with so much new information at a time, and without repetition to ingrain the essential content they need to remember, they’re more likely to forget what they review than retain it. Add a little sleep deprivation to the equation and you’ve got a recipe for poor cognitive performance!

Cramming may produce quick, short-term performance gains, whereas spaced studying feels like a harder, longer-term effort, but the payoff from spacing is deeper and longer memory retention, not to mention less net study time.

Unfortunately, the human brain favors those immediate rewards over the bigger, future ones.

In other words, students are choosing the strategy that feels most rewarding right now. They’re not making irrational choices so much as they’re making predictably human ones.

Is Teaching Students the Science of Studying Enough?

Short answer: it helps… but it’s rarely sufficient on its own.

Explaining the cognitive science of spaced repetition and retrieval practice absolutely matters. (And when you’re ready, check out this teacher’s guide we wrote about doing just that!) When students understand that spaced repetition outperforms cramming, they:

- Take study recommendations more seriously

- Roll their eyes less

- Feel respected as thinking adults

- Develop more accurate mental models of learning

In fact, research on metacognition suggests that helping learners understand how memory works improves self-regulation and strategic studying (Dunlosky & Metcalfe, 2009).

But here’s the uncomfortable truth:

Knowledge does not automatically produce behavior change.

Most adults understand basic nutrition science. We know vegetables are good. We know sugar spikes energy. We know sleep matters. Yet under stress, fatigue, or deadline pressure, impulse wins.

Study behavior operates under the same psychological forces.

Students are not ignoring spacing because they don’t believe it works. They’re cramming because:

- The exam date creates urgency

- Immediate performance feels rewarding

- The future benefit of spacing feels abstract

- No system is reinforcing daily effort

In other words, the environment is still optimized for cramming.

So if teaching the science isn’t enough, what is?

How to Actually Foster Daily Study Habits

Students respond to what gets rewarded and what gets checked.

If you want regular studying, your classroom must make it:

- Visible (it can be seen and tracked)

- Measurable (it has a clear standard)

- Easy to start (low friction, low activation energy)

- Connected to feedback or grades

One tool that makes all of this accessible to educators and achievable for students is digital flashcard apps like Brainscape, Anki, Memrise, and many others.

Let’s look a little closer at this tool and the strategies that consistently work, without turning your life into a grading nightmare!

1. Reward Frequency, Not Just Performance

Instead of grading only exam scores, allocate a small percentage of participation to study consistency.

For example:

- Credit for studying on 8+ unique days before an exam

- Credit for completing weekly retrieval sessions

- Credit for maintaining a minimum study streak

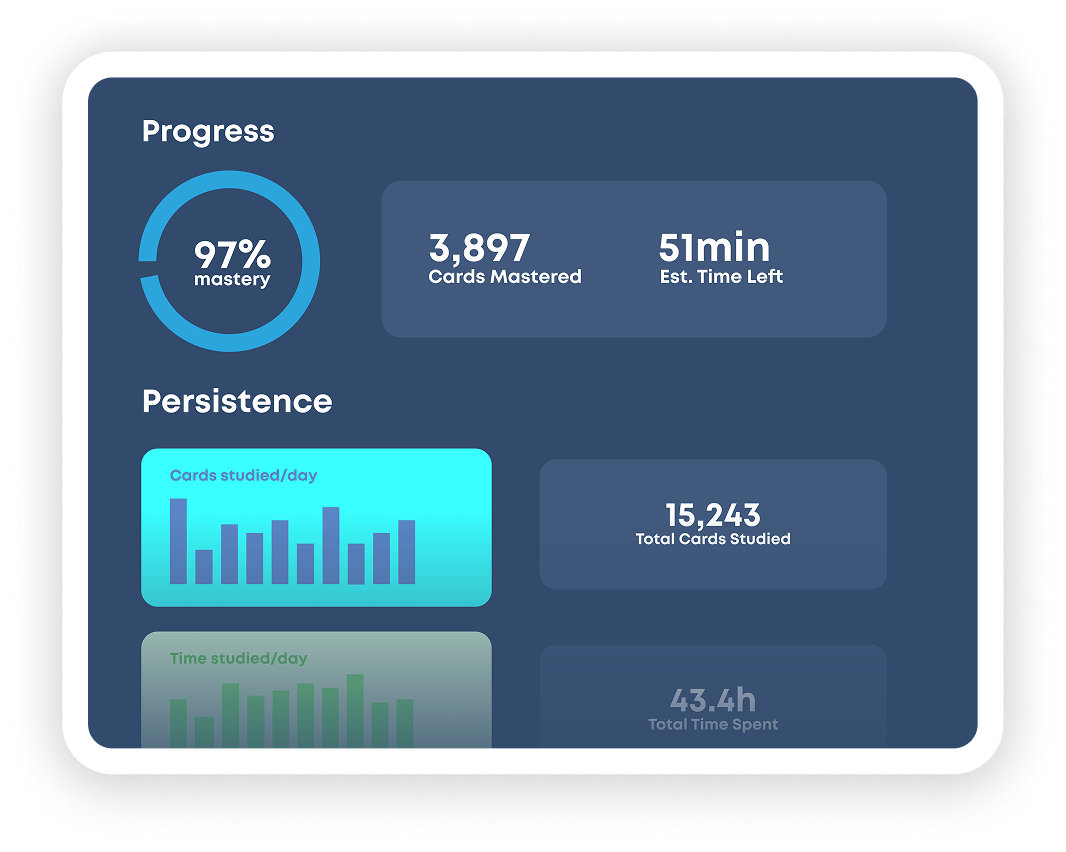

All of this is easy to do with a digital flashcard app like Brainscape, which records days and total cards studied, as well as study streaks (days studied in a row). This shifts the incentive from “last-minute intensity” to “steady effort.”

Even 5 to 10% of a grade tied to consistency can radically alter behavior.

2. Use Micro-Commitments

Large study goals are intimidating. Small ones are sticky.

Tell students:

- “Study 10 flashcards per day.”

- “Spend five minutes retrieving yesterday’s material.”

- “Create 5 flashcards on this topic.”

You can assign more, but the goal is not volume; it’s identity formation.

A student who studies 10 cards daily begins to see themselves as someone who studies regularly.

That identity is far more powerful than a one-time cram.

(And if students want to keep going after studying 10 flashcards or for five minutes, you should encourage them to! After all, the hardest part of studying is often just getting started.)

3. Build in Automatic Feedback

Behavior strengthens when feedback is immediate.

Low-stakes quizzes, retrieval warm-ups, or spaced flashcard systems give students instant signals:

- What they remember

- What they forgot

- Where to focus next

This closes the loop between effort and outcome, which is something cramming rarely provides.

4. Make Study Visible

If students know you can see their effort—whether through quiz results, retrieval logs, or flashcard app leaderboards—they are far more likely to engage.

Not because they fear punishment, but because accountability clarifies expectations.

5. Pair Cumulative Assessment with Daily Practice

When exams are cumulative (and students know they are) spacing becomes rational.

If yesterday’s material will appear again next month, cramming becomes inefficient by design.

Structure drives strategy.

The bottom line is this:

Teaching students why spaced repetition works is foundational. But designing a system that makes spaced repetition the path of least resistance is what changes behavior, which is why flashcard apps like Brainscape are such profoundly useful tools in any classroom.

When incentives, structure, and feedback align with cognitive science, regular studying stops being aspirational and starts being automatic.

Get Brainscape's Educator User Guide

Curious to learn more about how to introduce Brainscape into your physical or virtual classroom? Our Educator User Guide provides a detailed walkthrough of how to get set up. It'll also give you all the material you need to motivate adoption among your students, their parents, or the faculty of your school or college:

Other Evidence-Based Ways to Reduce Cramming

Beyond quizzes and consistency credit, here are a few strategies that reliably help:

Use exam wrappers. Have students reflect on how they studied, not just what they scored. This helps them connect choices to outcomes.

Break exams into smaller cumulative sections. Multiple smaller stakes reduce pressure and encourage continuous study.

Normalize imperfect recall. Students avoid regular study when they interpret difficulty as failure. Remind them that effortful recall is the point.

Provide study templates or routines. Decision fatigue is real. A simple weekly plan removes friction.

Make retrieval social to encourage accountability. Peer quizzing and collaborative recall can add accountability without adding grading.

All of these reinforce the same message: learning happens through repeated retrieval over time, not one heroic night of “studying.” Learning is a process, not a sprint.

(Read: How to Make Flashcards Students Will Actually Want to Study)

The Bottom Line for Educators

Students don’t cram because they want to. They cram because, well, they’re human! Also, many systems reward last-minute effort and make spacing feel like additional work.

The fix is not more lectures about study skills. It’s designing environments where regular studying is the path of least resistance.

Reward frequency. Track consistency. Reduce friction. Then let cognitive science do the work. Your students will learn more, plus they’ll learn how to learn.

Free Educator Resources For You:

- Brainscape Teacher’s Academy: Practical guides for implementing the cognitive science of learning and memory into your classroom, at scale

- “Tips for Teachers” YouTube Channel: Short, research-backed advice and classroom strategies

- The Cognitive Science of Studying: 16 Principles for Faster Learning: Discover how principles like retrieval practice, spaced repetition, and metacognition can help you learn faster and remember longer.

References

Cepeda, N. J., Pashler, H., Vul, E., Wixted, J. T., & Rohrer, D. (2009). Distributed practice in verbal recall tasks: A review and quantitative synthesis. Psychological Bulletin, 135(3), 354–380. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0015166

Dunlosky, J., & Rawson, K. A. (2020). Practice tests, spaced practice, and successive relearning. Educational Psychology Review, 32, 207–228. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10648-019-09510-6

Roediger, H. L., & Karpicke, J. D. (2006). Test-enhanced learning. Psychological Science, 17(3), 249–255. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-9280.2006.01693.x

Soderstrom, N. C., & Bjork, R. A. (2015). Learning versus performance. Perspectives on Psychological Science, 10(2), 176–199. https://doi.org/10.1177/1745691615569000

Steel, P., & König, C. J. (2006). Integrating theories of motivation. Academy of Management Review, 31(4), 889–913.