This article is part of Brainscape's Science of Studying series.

Picture a slot machine. Not because learning should feel like gambling (“maybe I’ll remember this, maybe I won’t”) but rather because your brain lights up for the same reason a Vegas regular keeps spinning the wheel: the thrill of not knowing what might happen next. That tiny jolt of uncertainty is surprisingly powerful. It drives attention, action, and often…obsession.

The principle of unpredictable reinforcement is called variable rewards, and it shows up in places far beyond casinos. Social media feeds, video games, email notifications, sports, and yes, even study habits rely on it. Understanding how it works can help you design learning routines that feel more naturally motivating.

And being motivated to study? Well, that’s the Holy Grail all students search for!

In this article, we’ll explore the cognitive science behind variable rewards and how digital flashcard systems like Brainscape harness it to sustain long-term study engagement. So, if you’ve ever wondered why some tools feel “sticky” in a good way, this is the science behind it.

Let’s get nerdy…

What Are Variable Rewards?

Variable rewards are outcomes delivered on an unpredictable schedule. Instead of receiving the same reward every time you perform a behavior, you get it only sometimes. The key is that you never know exactly when the reward will appear.

This is exactly how slot machines work. In spite of the fact that you almost NEVER win—and when you do, it tends to be piffling amounts—millions of people all over the world sink billions of dollars into them.

Because of that 1 in a 49 million chance you might hit the big jackpot.

In psychology, this is often described through the variable-ratio reinforcement schedule, an obnoxiously long descriptor that essentially means: where a reward is tied to an action, but comes at unpredictable intervals.

For example, you may get a “like” on your social media post after three views, then twelve, then one hundred. The reward is linked to your behavior, but its timing is inconsistent. This unpredictability increases engagement because your brain keeps “checking” for the next possible payoff.

Of course, in daily life, variable rewards do not always involve prizes or points. They can also be moments of progress, insights, wins, or even emotional satisfaction. It’s not the rewards themselves that drive motivation (although of course they’re nice).

It’s the unpredictability itself.

Where Did the Idea of Variable Rewards Come From?

The concept of variable rewards grew out of behaviorist psychology in the mid-twentieth century. B. F. Skinner’s experiments at Harvard demonstrated that pigeons and rats learned behaviors more quickly and persistently when rewards were delivered unpredictably. These findings appeared repeatedly in Journal of Experimental Psychology publications and helped lay the groundwork for modern reinforcement theory.

Later researchers expanded the idea into human behavior. Psychologists such as Robert Amsel, Albert Bandura, and Michael Zeiler refined models of partial reinforcement, while more recent studies have integrated neuroscience to explain why unpredictability activates dopamine pathways more strongly than predictable rewards.

Today, variable rewards are studied across behavioral economics, habit formation, user-experience design, and educational psychology. Their influence is so widespread that nearly every modern app or platform intentionally or not, uses some version of a variable reward mechanism.

And, yes, the flashcard app Brainscape is no different.

How Do Variable Rewards Work, Cognitively?

Variable rewards primarily affect the brain through dopamine, a neurotransmitter involved in motivation, attention, and learning from feedback. Dopamine, contrary to how it is popularly characterized in the media, is not actually a “pleasure chemical.” It is a prediction chemical. It spikes not when you get something good, but when you think you might get something good.

In other words, dopamine production is triggered when you anticipate a reward.

(I relate to this most viscerally when it comes to snacking. Almost always, the idea of a tub of Ben & Jerry’s ice-cream is better than the reality. Sure, that first spoon or two is delightful. But halfway through the tub, my dopamine plummets past my soaring insulin levels, like two bullet trains passing in opposite directions.)

But back to the science. When rewards are unpredictable, the brain becomes hypersensitive to cues that signal potential payoff. This heightened anticipation increases:

- Engagement

- Effort

- Persistence

- Attention to detail

- Emotional investment

Neuroscience research has shown that variable reinforcement amplifies activity in the ventral striatum and midbrain reward circuitry. In plain English: uncertainty enhances learning because your brain records the details of what happened just before a surprising outcome. And so, in an effort to learn how to replicate those results, your brain pays closer attention.

This is why unpredictable feedback is so compelling. The “maybe this time” feeling is both biological and adaptive. It helps organisms respond dynamically to environments where rewards are not guaranteed.

Here are the components of a good variable reward system:

- Unpredictability: The reward needs to occur on an irregular schedule, creating anticipation.

- Contingency: There needs to be a connection between action and reward, even if the timing is uncertain.

- Emotional spike: Unpredictable rewards generate stronger dopamine responses.

- Reinforced repetition: The unpredictability increases persistence and continued behavior.

- Attentional sharpening: The brain encodes cues more deeply when outcomes vary.

- Feedback learning: Variable rewards strengthen associations between behavior and desired results.

- Motivational resilience: Behaviors reinforced variably are harder to extinguish than those reinforced consistently.

Why Do Variable Rewards Matter for Learning, Teaching, and Memory?

Variable rewards matter for learning because the uncertainty keeps the brain engaged Remember: that heightened anticipation increases engagement, effort, persistence, attention to detail, and emotional investment, all of which are powerful ingredients in learning.

A predictable learning routine, on the other hand, can become monotonous. When feedback, difficulty, or progress varies, learners tend to stay mentally active.

Some ways this shows up:

1. Difficulty that fluctuates improves skill building.

If every learning task feels equally easy or equally hard, the brain checks out. Variation creates challenge, novelty, and micro-wins.

2. Unpredictable successes increase motivation.

Those moments when a difficult question suddenly “clicks” create a burst of satisfaction. Because they are not guaranteed, they feel meaningful.

3. Feedback that varies strengthens memory.

Retrieval practice is more effective when the brain cannot predict exactly when it will be tested. That small element of surprise deepens encoding.

4. Mixed practice boosts transfer.

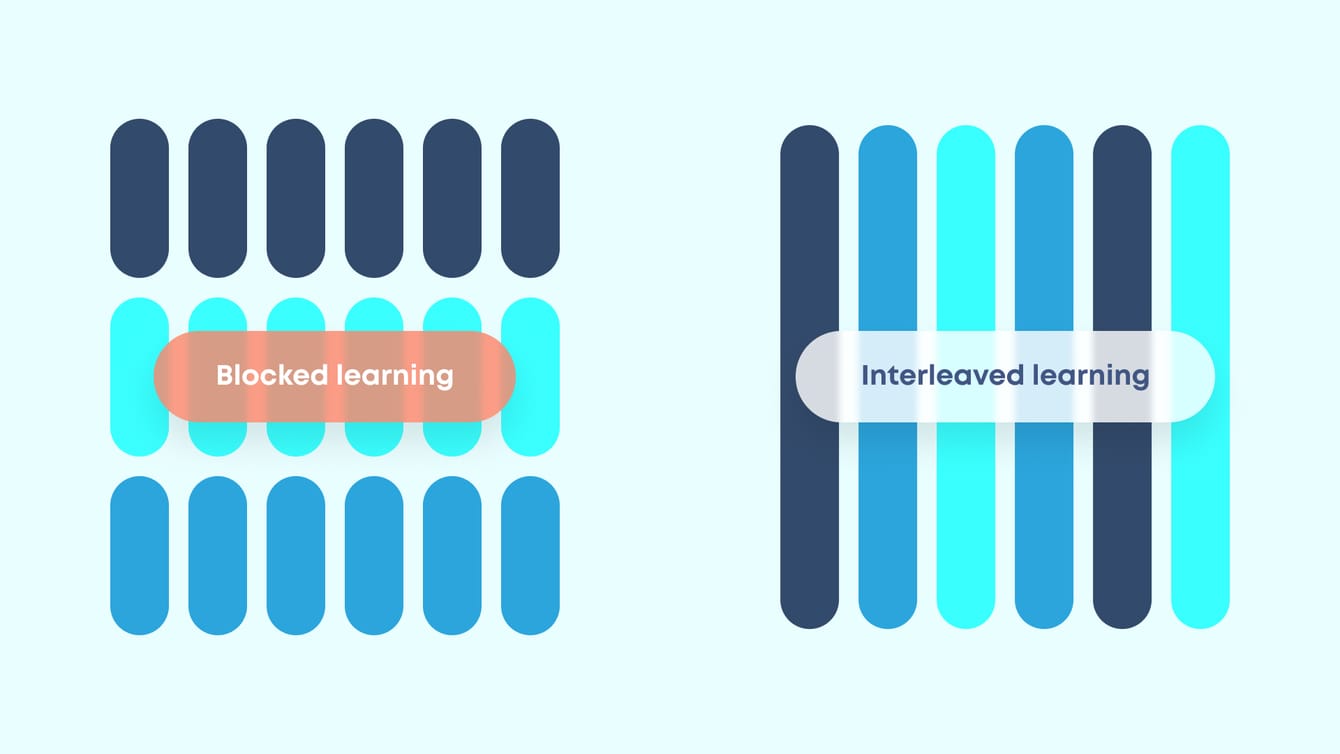

Shifting between topics or question types (a practice called interleaving study) keeps learners alert and strengthens flexible thinking.

5. Progress that unfolds in unpredictable increments feels more rewarding.

Sometimes you understand a concept slowly, sometimes quickly. The variability keeps you emotionally invested.

These effects make variable rewards particularly relevant for today’s learners (and educators) who must sustain effort across long learning processes. Whether preparing for a major exam or learning a new language, variability keeps motivation alive.

How Can Learners and Educators Apply Variable Rewards?

You do not need to gamify your study life or install elaborate reward systems to harness the learning power of variable rewards. Instead, you can leverage small, natural elements of unpredictability that spark engagement. Here are some great tools and ideas to accomplish that:

Digital flashcards with spaced repetition features.

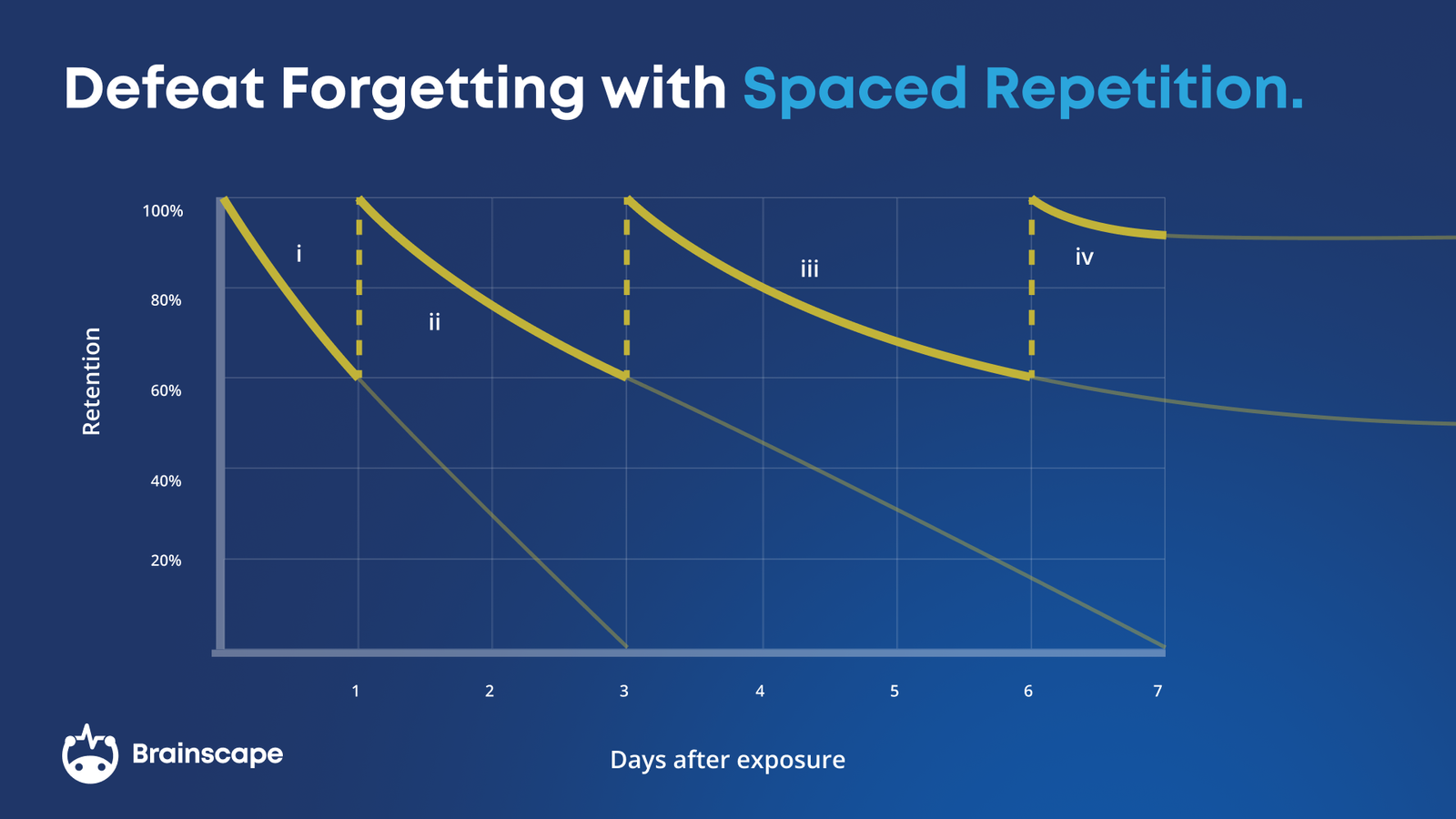

Spaced-repetition is the repeated exposure of a learner (you) to concepts when you were just about to forget them. In other words, if you learned about mitosis in class today, you’d need to review it again within 24 hours, and then again and again at increasingly longer periods of time, until it becomes permanently banked in your memory, like we see in the following graph…

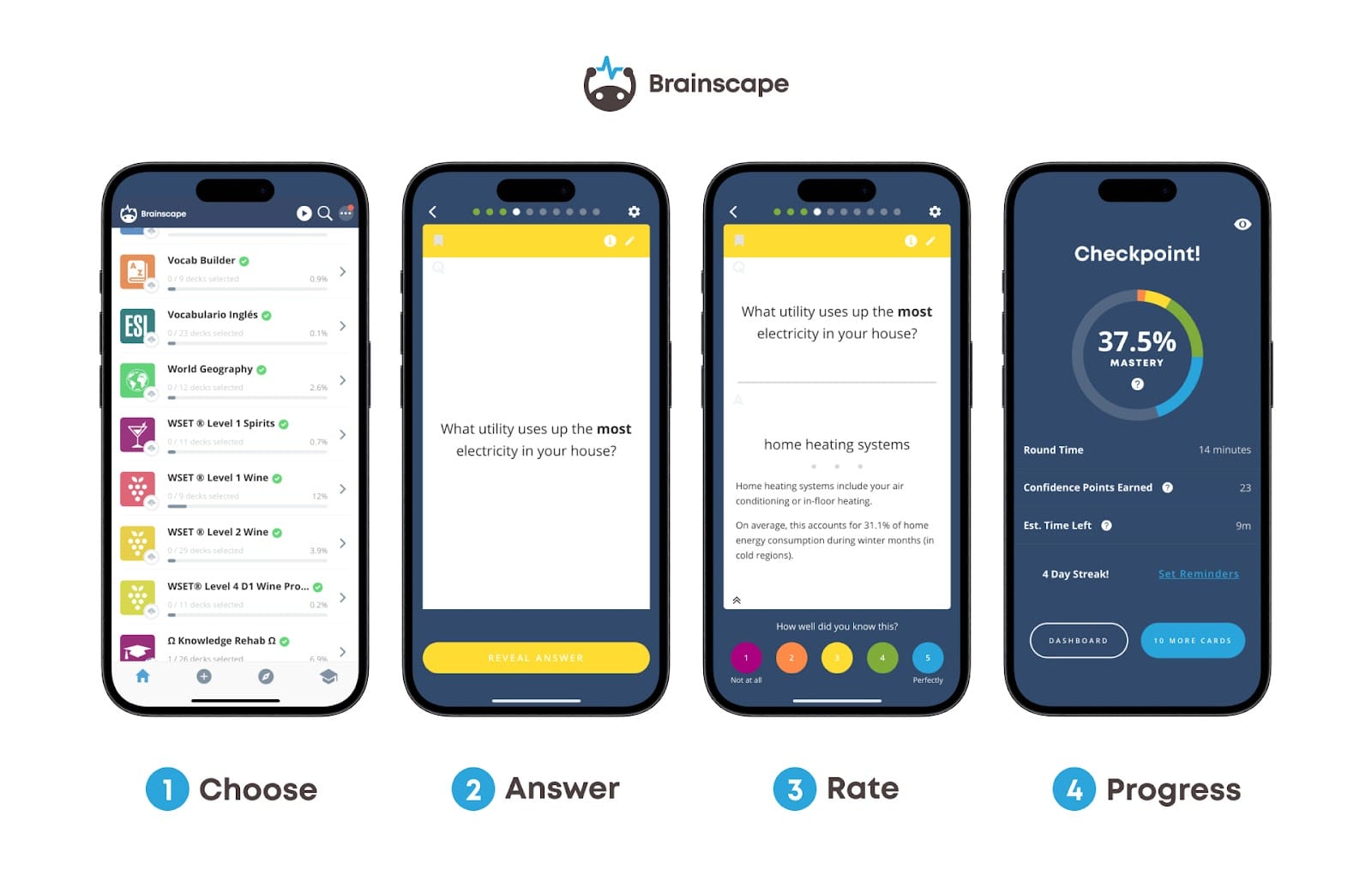

Flashcard apps like Brainscape apply this principle very easily because they (1) break subjects down into atomic concepts that can then be delivered to you (2) via an algorithm that’s programmed with a spaced repetition schedule. By varying the intervals between reviews, learners cannot predict exactly when a flashcard will reappear. This built-in uncertainty strengthens retrieval effects and increases attention.

This, among the many other cognitive science principles they harness, is why flashcards are such a powerful tool for fast learning.

Mix up your study order.

Instead of moving through material linearly, shuffle topics or question types. Interleaving introduces beneficial unpredictability. (Flashcards make this easy.)

Vary difficulty intentionally.

Alternate between easy, moderate, and challenging questions. The occasional tough one heightens dopamine responses when you succeed.

Study in short, variable bursts.

Changing session lengths prevents routines from becoming dull and encourages more consistent engagement.

Incorporate surprise checks.

Give yourself or your students occasional pop quizzes, quick retrieval prompts, or flashcard challenges. The unpredictability makes the practice feel more alive.

Reward progress inconsistently.

Rather than giving yourself a treat every time you hit a study goal, celebrate unpredictably: sometimes after finishing a topic, other times after a particularly hard success.

Use reflection moments.

Ask: What surprised me today? Where did I get an unexpected win? These micro-surprises reinforce motivation.

The goal is not to manipulate your brain but to work with it. Variability is inherently rewarding. By weaving natural unpredictability into learning routines, you can make motivation more sustainable for yourself or your students.

A Final Word on Variable Rewards

Variable rewards explain why humans are drawn to unpredictability. (How else do you think narcissists get all the girls?) Our brains evolved to pay attention when outcomes are uncertain, and this attention fuels motivation. When applied thoughtfully, variable reinforcement creates learning environments that feel more dynamic, more engaging, and more satisfying.

This is one of the many cognitive principles quietly embedded into study tools like Brainscape. Digital flashcard systems that use spaced repetition and retrieval practice naturally harness the motivational power of variability, turning decades of cognitive science into daily study routines that don’t feel like a chore.

Get Brainscape's Educator User Guide

Curious to learn more about how to introduce Brainscape into your physical or virtual classroom? Our Educator User Guide provides a detailed walkthrough of how to get set up. It'll also give you all the material you need to motivate for its adoption amongst your students, their parents, and/or the faculty of your school or college:

Additional Reading

Don’t stop here! Keep nerding out over how your brain actually works with these awesome reads:

- What Is Confidence-Based Repetition (& How Can I Massively Boost Grades)?

- The Science of Social Motivation: Why We Work Harder When People Are Watching

- What is Active Recall? How to Use It to Ace Your Exams

For even more articles on how to harness cognitive science to improve learning, focus, and memory, check out our ‘Science of Studying’ hub.

Variable rewards can make a routine feel easier to return to, but you still want that effort to go into study behaviors that actually build memory. If you want a quick, classroom-ready way to steer students away from passive habits and toward active ones, the infographic below makes that switch obvious.

References

Aitken, M. R., Dickinson, A., & Shanks, D. R. (2020). Prediction error and reinforcement learning. Quarterly Journal of Experimental Psychology, 73(7), 1103–1125. https://doi.org/10.1177/1747021820904771

Bryce, C. A., & Floresco, S. B. (2021). Perturbations in reward-related decision-making induced by stress: Evidence from rodent studies. Neurobiology of Stress, 14, 100294. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ynstr.2021.100294

Garrison, J., Erdeniz, B., & Done, J. (2021). Prediction error and reward-seeking: A systematic review. Neuroscience & Biobehavioral Reviews, 120, 141–161. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neubiorev.2020.11.013

Schultz, W. (2017). Reward prediction error. Current Biology, 27(10), R369–R371. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cub.2017.02.064

Skinner, B. F. (1953). Science and human behavior. Macmillan. (Open-access via B. F. Skinner Foundation) https://www.bfskinner.org/science-and-human-behavior

Stauch, B. J., Heissel, A., & Otto, A. R. (2022). Cognitive control, reward processing, and mental effort: A neurocomputational perspective. Psychological Review, 129(4), 729–754. https://doi.org/10.1037/rev0000320

Wilson, R. C., Bonawitz, E., Costa, V. D., & Ebitz, R. B. (2021). Balancing exploration and exploitation with information and randomization. Current Opinion in Behavioral Sciences, 38, 49–56. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cobeha.2021.01.002