Boredom vs. Motivation (What Teachers Are Up Against)

As teachers, we see this every day. When students are home feeling bored, what pulls them in first: going out to play sports with a friend, or opening a book to study for a test? For most students, the pull toward movement, games, and social interaction is immediate. From an evolutionary biology perspective, this makes perfect sense.

Humans evolved to learn biologically primary skills—movement, language, social interaction—because they were essential for survival. These activities naturally activate the brain’s reward systems and feel intrinsically motivating (Deci & Ryan, 1985; Ryan & Deci, 2000; Geary, 2008).

By contrast, the core purpose of school is to teach biologically secondary skills—reading, writing, mathematics, scientific reasoning—which do not automatically feel rewarding. In fact, if we compress human history into a single day, formal schooling appears only in the final minutes.

We don’t need school to learn to throw or play: put a child in a room with three coloured balls, and they will instinctively play, not memorise the colours. School exists because secondary skills require effort and no built-in intrinsic motivation.

From a teaching perspective, successful learning therefore depends on helping students build habits and systems that make effortful thinking stick.

The Core Job of School: Learning That Lasts

We could debate the wider social purposes of schooling—citizenship, character, employability—but at its core, the main job of school is learning: acquiring knowledge that is retained and usable later.

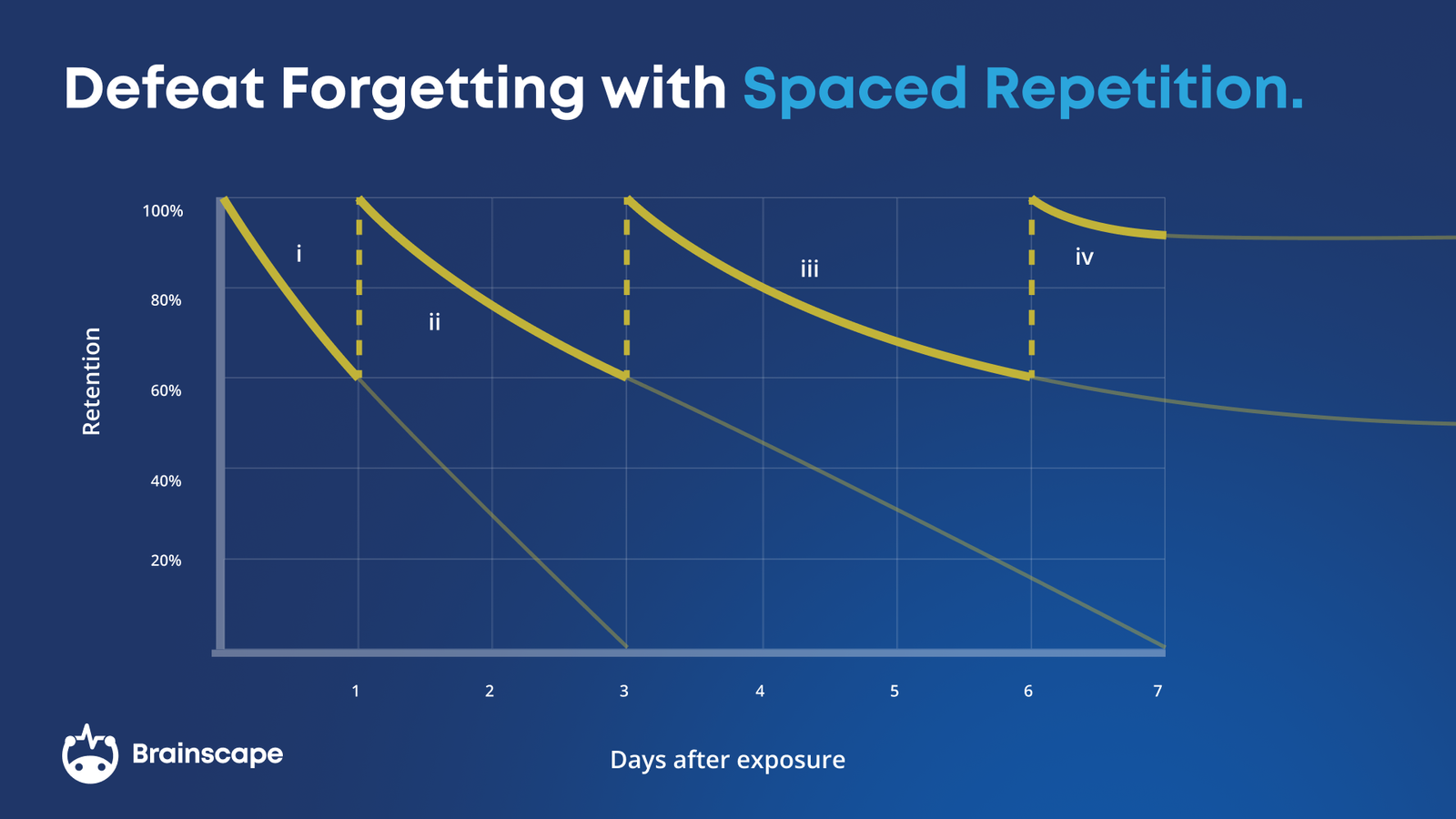

Cognitive scientists have identified strategies that make learning stick. Robert Bjork calls the most powerful of these desirable difficulties; learning strategies that feel harder in the moment but lead to stronger, more durable learning over time (Bjork, 1994; Bjork & Bjork, 2011).

A useful analogy for teachers is to think of the brain like a muscle.

In the gym, lifting heavier weights and pushing close to failure produces long-term gains. Many people quit before seeing results because progress is slow and largely invisible. Learning works the same way.

Spacing practice, retrieving information from memory, varying conditions, and struggling before being shown the answer all feel uncomfortable for students, but they are precisely what build durable knowledge.

Thorndike and the Law of Effect (Why Students Avoid Effective Study)

Over 100 years ago, Thorndike’s puzzle box experiments with cats laid the foundation for understanding habits. Hungry cats had to perform specific actions, like pulling a lever, to access food. Over repeated trials, correct actions became faster, while ineffective behaviours faded.

Thorndike’s Law of Effect states:

“Responses that produce a satisfying effect in a particular situation become more likely to occur again in that situation, and responses that produce a discomforting effect become less likely to be repeated.” (Thorndike, 1911).

This helps explain a familiar classroom pattern. Students naturally gravitate toward easy, immediately rewarding study strategies and avoid challenging ones, even when those challenging strategies are far more effective in the long term.

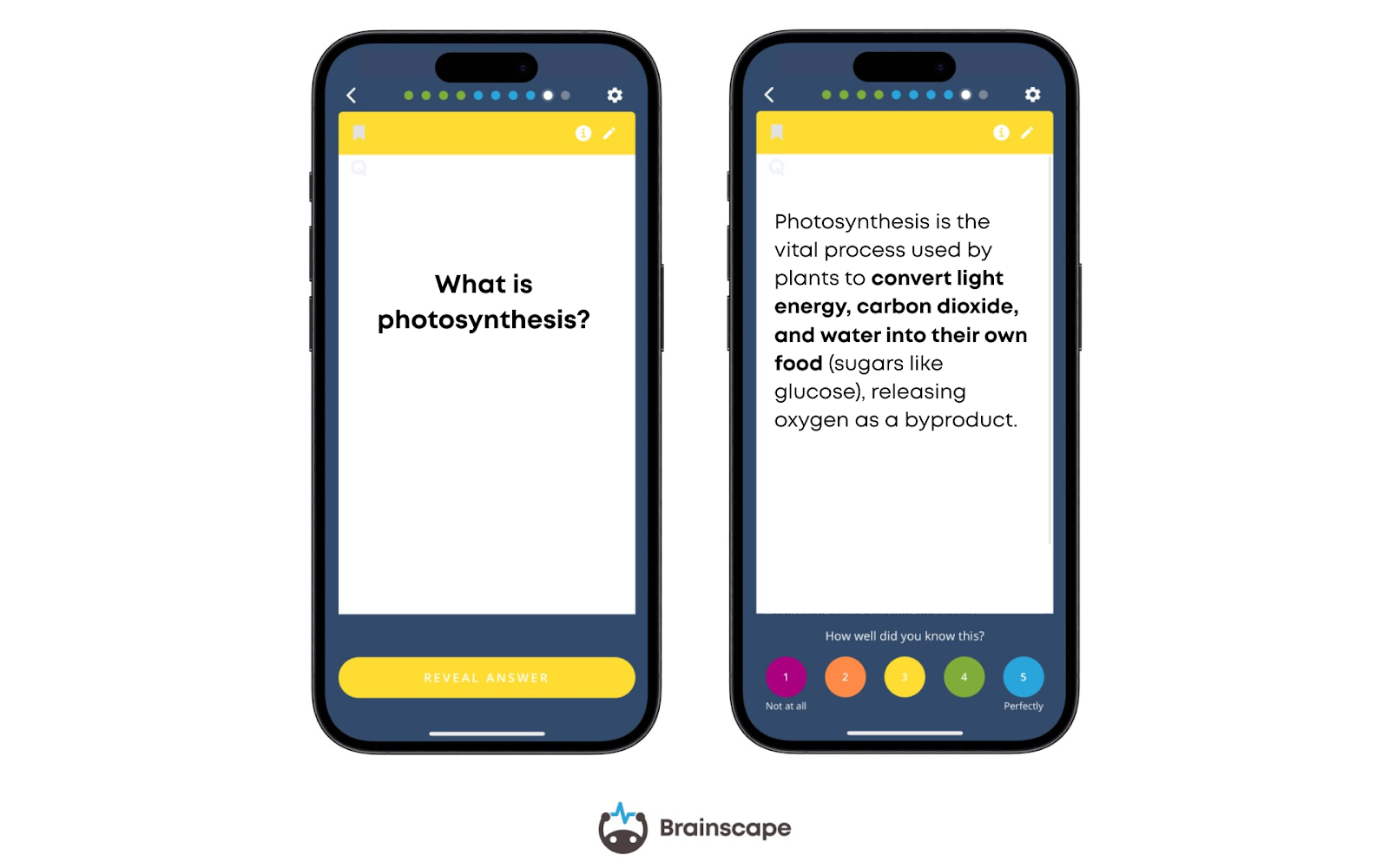

Why Flashcards Can Be Hard, but Powerful

From a teacher’s perspective, this is where flashcards often fail, not because they are ineffective, but because they are uncomfortable.

After a long day, the last thing students want is to confront their mistakes. Well-designed flashcards do exactly that.

- Too easy: like lifting weights far below your comfort zone: little impact.

- Challenging: highlight mistakes and engage deep learning: uncomfortable but effective.

Without support, students often abandon flashcards not because they “don’t work,” but because they work too well at exposing what isn’t yet secure.

How Teachers Can Help Students Build a Lasting Flashcard Habit

Many people still go to the gym despite not seeing immediate rewards, and the same principle applies to learning. For students to persist with flashcards, teachers need to help them understand and shape the habit cycle: cue → routine → reward. Consistent pairing strengthens automaticity over time (Wood & Neal, 2007; Lally et al., 2010).

Here are several practical ways teachers can support this process.

1. Help Students Set a Clear Cue

- Encourage scheduling study (with app notifications) at the same time each day.

- Suggest placing study apps or materials where they are immediately visible.

- Use environmental nudges to reduce reliance on willpower (Thaler & Sunstein, 2008).

2. Make the Routine Feel Easy

- Reduce friction where possible: for example, encourage students to block social media apps or move them into a password-protected folder, and plan short, focused sessions.

- Emphasise starting small, reviewing just a few cards still counts on busy or tiring days.

3. Encourage Pairing with a Reward

- The brain releases dopamine in anticipation of rewards. Students are more likely to persist if flashcard sessions are followed by something enjoyable, like a snack, a walk, or a short break.

4. Teach Implementation Intentions

- Specific “if–then” plans make follow-through more automatic: “When I finish dinner, then I will review ten flashcards” (Gollwitzer, 1999).

5. Help Students Optimise Their Environment

- Encourage students to avoid study spaces strongly associated with relaxation or entertainment.

By deliberately shaping cues, routines, and rewards, teachers can help students turn effortful, initially unrewarding study practices into lasting flashcard habits, just as persistent gym-goers turn workouts into lifelong routines!

Before you go, watch this video on the potential downsides of flashcards...

References

Deci, E. L., & Ryan, R. M. (1985). Intrinsic Motivation and Self-Determination in Human Behavior.

Ryan, R. M., & Deci, E. L. (2000). Intrinsic and Extrinsic Motivations: Classic Definitions and New Directions. Contemporary Educational Psychology.

Geary, D. C. (2008). An Evolutionary Perspective on Learning (for the mismatch between evolved brains and school learning)

Bjork, R. A. (1994). Memory and metamemory considerations in the training of human beings. In J. Metcalfe & A. Shimamura (Eds.), Metacognition: Knowing about knowing (pp. 185–205). MIT Press.

Bjork, R. A., & Bjork, E. L. (2011). Making things hard on yourself, but in a good way: Creating desirable difficulties to enhance learning. In M. A. Gernsbacher, R. W. Pew, L. M. Hough, & J. R. Pomerantz (Eds.), Psychology and the real world: Essays illustrating fundamental contributions to society (pp. 56–64). Worth Publishers.

Thorndike, E. L. (1911). Animal Intelligence: Experimental Studies. Macmillan.

Gollwitzer, P. M., & Sheeran, P. (2006). Implementation intentions and goal achievement: A meta-analysis of effects and processes. Advances in Experimental Social Psychology, 38, 69–119. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0065-2601(06)38002-1

Wood, W., & Neal, D. T. (2007). A new look at habits and the habit–goal interface. Psychological Review, 114(4), 843–863. https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-295X.114.4.843

Lally, P., Van Jaarsveld, C. H. M., Potts, H. W. W., & Wardle, J. (2010). How are habits formed: Modelling habit formation in the real world. European Journal of Social Psychology, 40(6), 998–1009. https://doi.org/10.1002/ejsp.674

Thaler, R. H., & Sunstein, C. R. (2008). Nudge: Improving Decisions About Health, Wealth, and Happiness. Yale University Press.